3 April 2012

Copyright © 2012 by P. A. Ritzer

I called in to the Laura Ingraham show on 22 March to comment on the issue of living together before marriage. Basically, I said: Women need to get a clue; if a man loves you, he’ll wait. As I used to ask my students: when you live together, how do you break up? You still have the rent and the electrical bill. You are more likely to remain in an unhealthy relationship. It comes down to the fact that love is not a feeling but an act of the will. It is a giving of the self that involves commitment. Feelings rise and fall, that is why you need commitment.

All we need to do, especially during Holy Week, is to take a look at a crucifix: the greatest act of love ever, and it did not feel very good.

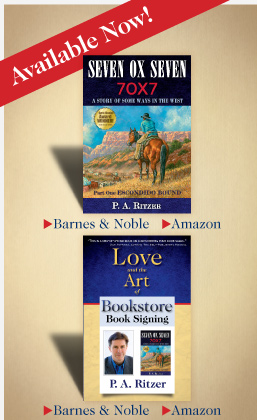

In Seven Ox Seven, Part One: Escondido Bound, Tom has to grapple with the question of love in light of romantic feelings that rise up in response to meeting a beautiful woman. Here is how he works it out in pages 82-86.

Copyright © 2007 by P. A. Ritzer

Julie flooded back—from where she had been occupying a good deal of the area behind it—to the forefront of Tom’s mind. In truth, she had occupied the greater part of his mind for most of the time since he had first seen her, and had at least wafted around somewhere in the back or bottom of his mind when she had not been occupying the greater part. It was not as if he actively thought of her. He did not need to think of her. It was less voluntary than that. He would have had to think to keep her out. There was a naturalness to the way she flooded his mind. Thinking of her was a natural reaction to the stimulus of her, and that thought had a naturally sensual character to it. The natural scent of her hair and skin, subtly enhanced by perfume, again delighted his sense of smell, in memory, intoxicating his mind through that most evocative of the senses. Her slender, lithe figure and the way that she moved played upon him in a way that no dance or drama could or, for that matter, could any imaginable movement of even the most graceful of the creatures of land, sky, or sea. Again he saw her eyes and, starting with those portals open wide to him, again ventured upon that journey into her beauty. Again her rich silken hair rested against the side of his face, as it had when they had danced; again the softness of her cheek glided beneath the light brush of his hand; again her delicate hands lightly enclosed his own.

He chuckled at how she had immediately attracted him and at how she still had a sensual hold on his mind. She was not the first to so affect him, and he doubted that she would be the last. He knew, from experience, that her absence would allow time to continually diminish the superficial though pervasive place she presently held in his mind, and he knew that, in this case, absence was the most prudent policy.

To get involved with a girl like Julie would be to give himself over to insecurity, because, since they did not appear to share common values, she could just as easily be interested in any other man who suited her (and probably would be), and he in any other woman. Julie was pretty enough to demand as much commitment as the willing man could afford, however illicit. Her knowledge of her power over men as an object of desire, and the pleasure such power obviously gave her, would only add to the insecurity of the relationship, as it would keep her ever watchful for that future man, better than the rest, who, too, would fall prey to her beauty and her charms. Judging from what he had seen of her values, Tom knew that he would not be this ultimate man, and he wondered whether any man ever would be, before her beauty would gradually succumb to the cosmetic applications so evident, at the Lady Gay, upon the faces of older members of her occupation. Regardless, such insecurity in a relationship could well lead to possessiveness or, paradoxically, to its contrary, disregard. Possessiveness could eventually lead to anger and resentment, disregard to indifference.

Tom considered further the development of a relationship founded on such shallow footings. How many times had he seen a man fall “head over heels” for a woman, only to see him, after that relationship had ended (and the fellow had been all but broken in half), fall equally in love with another woman nothing like the last. Such a thing could not then be love, Tom maintained, but some baser attraction. Love, instead, elevates desire between a man and a woman to its proper place, in a way that sets the human apart from the horse or the cow. Love elevates that desire into a consciousness of the need for moral and practical compatibility, which does not allow one to fool oneself into believing that selfish obsession with another can be love. This special love between a man and a woman must then require something of reason, which sets the human apart from the beast, to elevate this desire. The human creature must let reason rule desire and let love rule reason for them to be properly directed. Such is required by the dignity appropriate to the rational creature.

Therefore, Tom would never have considered that it was love that kept Julie in his mind. He had seen some men—and not just the young fellows fresh away from home and under the influence of drink—make that mistake often enough. But Tom knew that any fellow who would believe that he was in love in such a case, or even in a case more involved though equally shallow, was missing something. Otherwise, how could a man feel similar romantic feelings for different women, very unlike each other and of very different minds from the man himself?

No, such could not be love but merely infatuation. Tom knew love, and he would not have elevated infatuation to that height. It was because he knew love that he was also wary of over-romanticizing love between a man and woman. Love was plainer than glamorized infatuation, and yet, more profoundly beautiful in its plainness. It had its share of hardship, hard work, and pain. Love had a nakedness about it, compared to which the nakedness of infatuation was but a woefully shallow imitation. The nakedness of love could not be satisfied by the merely sensual. The nakedness of love demanded far more because it was far more: because it was the complete exposure, the complete sharing, the complete gift of the self, not just of the body. (And, in truth, given that the body is an essential component of human nature, one could never truly share the body without, at least to some degree, sharing the self, licitly, to one’s benefit, or illicitly, to one’s detriment.) The nakedness of love demanded commitment, with all that that word denoted and connoted, and a commitment not just to the other, but to the Other, Who is the Source of all love, Who is Love itself.

This awareness, on Tom’s part, always brought him around to his belief that there must be far more than just the sensual attraction between a man and a woman before it is appropriate to move further into the sensual realm of the relationship. There must be something profound that puts the sensual in its proper place and elevates it. There must be a singular affinity between the minds and souls of the man and woman, an affinity that draws them toward the commitment of love. There it was again, commitment, an act of the will, an act of the will that is the gift of the self. That is love: an act of the will that is the gift of the self! The commitment of love, in this singular case, must be Matrimony, the only commitment that, as a sacrament, provides the grace for a man and woman to share the nakedness of the Garden of Eden while yet in a fallen world. The grace of the sacrament assures that, rather than become a selfish taking, the sensual intimacy can be a selfless giving: to spouse, to God, to the children thus begotten. Hence, the Sacrament of Matrimony is the only commitment worthy of the ultimate sensual intimacy, an intimacy through which a man and woman become one body and, as such, enjoy the profound privilege and responsibility of participating in and sharing in God’s creation of another human being. It is in this commitment of the Sacrament of Matrimony that a man and woman are most capable, by design, of accepting their responsibility to raise to adulthood the human beings created through their union.

Given all that, Tom believed that it should follow, then, that a man should test his attraction to a woman for that affinity that draws a man and a woman into the Sacrament of Matrimony. He should do so because the attraction could lead to union, and union to procreation. The procreative result of this union is another human being, another material and spiritual creature with the capacity of union with the Infinite. Thus, the union of man and woman must command a most profound respect and commitment, because the procreation and upbringing of the product of that union, a child with a supernatural destiny, must carry a most profound responsibility.

He knew that no such affinity could exist between Julie and him. And yet she remained in his mind. He saw again the lose strands of her hair around her pretty ear and against her graceful neck. He saw again those long lashes and looked into those dark eyes. And again he knew that he could have been lost in those eyes, and that, past a certain point, he could have dissolved into her and enjoyed great pleasure in doing so, but for some little guide in him, a guide that could reach out and offer him the opportunity to return to shore from those waters into which he had begun to wade. Ah, but for this guide, conscience, what the contemporary Briton John Henry Newman would call “the aboriginal vicar of Christ.” Yes, but for this guide, what further evil might be introduced into this world under the guise of pleasure.

In this way, Tom’s mind examined the reality of the day against revealed truths and personal conclusions. That examination was part of a river of analytical thought that flowed through his mind seemingly involuntarily and almost incessantly. This flow of analytical thought was something Tom took for granted: he knew no other way.

“Hmph,” Tom sighed out loud, in a kind of muffled chuckle. “All this from dancin’ with a dancehall girl,” he thought.

But he knew it was more than that. All human relationships have a beginning, and how and why they begin determine to greater and lesser degrees how and where they proceed. Julie may not have technically been a cyprian, like some of the dancehall girls, but she saw no problem with accepting pay to show her affections. And Tom knew that once a person decided that her affections were for sale, the object of those affections would be the highest bidder, whether the bid was in money or some other variety of tender.

Nevertheless, though he had thus disposed of this potential relationship, it was the nature of Tom’s mind that, no matter what other thoughts ran through it, thoughts of Julie drifted around behind them and, often enough, advanced to the front, until he fell off to sleep.

The Republican Convention and PBS

© 2012 by P. A. Ritzer

29 August 2012

As I watched one speaker after another intelligently and engagingly put the lie to the Obama and Democratic Party record and talking points, I had to wonder at the PBS team covering the event. First of all, I would have rather heard and seen Janine Turner and Nikki Haley and anyone else I missed when the PBS team deemed that their . . . what? . . . “commentary” and “analysis” should take priority over the contributions of the real players in this one-time event. Among other things, I wondered if the amply seasoned partisan commentators Gwen Ifill, Judy Woodruff, and Mark Shields, and their token conservative–so suited to the role that he writes for the New York Times and was once inspired to prophesy about an inevitable Obama presidency while staring at the crease in Obama’s pants–David Brooks still made a pretense of objectivity.

Regardless, I thought back to an earlier time when I was glad of PBS Republican Convention coverage. It was 1984, and I had finally landed on PBS after hurriedly clicking through the four available channels. Why the rush? Well, because I had noticed that, off in the distance behind John Chancellor droning on to Tom Brokaw, it appeared that Jack Kemp was speaking. No, the networks would not talk over one of the most dynamic and popular Republicans of the day. But, sure enough, when I landed on PBS, there was Kemp. But they would not do that to Jeane Kirkpatrick, the keynote. Sure they would, and at least John and Tom did. Again, I found her on PBS. So, two of the brightest stars of the night, including a brilliant woman who was at the time still a Democrat who would switch to the Republican Party the next year, were kept from the view of the public by tedious liberal commentary. I remember that Paul Harvey–this was still a few years before Rush Limbaugh burst onto the scene and signaled the beginning of the end of the liberal media monopoly, for now–the next day mentioned this abuse of power by the networks and how he would tune to PBS from that time on for coverage of the Republican Convention.

So, I did just that, as well. And during a later campaign, when MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour was the only news program that, despite its liberal bias, would at least bring on guests representing the opposing point of view, I watched their campaign coverage. I remember the glowing backgrounder report on the Democratic Party, stretching well past Martin Van Buren and Andrew Jackson and the Albany-Richmond Axis all the way back to Thomas Jefferson. No mention of slavery, the Dred Scott Decision, the Ku Klux Klan, lynching, the black codes, disfranchisement, Jim Crow, opposition to women’s suffrage. Huh. All right. Well, anyway, I looked forward to the backgrounder on the Republican Party. I believe it was Judy Woodruff who delivered it. As I remember, it started out with how “the modern Republican Party” started with Richard Nixon. What? Not conceived as a reaction to the Kansas-Nebraska Act and its extension of slavery? No Ripon? No Abraham Lincoln? No Emancipation Proclamation? No Frederick Douglass? No Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments? No civil rights laws? No Ulysses S. Grant? No Susan B. Anthony, women’s suffrage, and the Nineteenth Amendment? No Theodore Roosevelt? No Calvin Coolidge? No Dwight D. Eisenhower? No century-long battle against the Democrats to secure civil rights for African-Americans? No, it was Richard Nixon. The “modern” Republican Party started with the most discredited, rightly or wrongly, Republican president in history. How convenient.

But people are beginning to know better today. The new media is shredding the monopoly of the liberal media, though many–including the Republican establishment–have not yet fully realized it. And thus people have access to sources that belie what was spoon-fed to the public by the old media. And the media did look old on that PBS panel. Nevertheless, they still try, and feisty old Mark Shields thought he had really got one of the guests when he pointed out that the Morrill Act and the Homestead Act, both first passed in 1862, were Republican “government programs.” Yes, but these were not liberal Democratic programs like those of the New Deal and the Great Society designed to create dependence on an ever-expanding government. To illustrate my point, I refer to the following excerpt about the Homestead Act from Seven Ox Seven, Part One: Escondido Bound, pp. 55-56:

In the case of homesteading, the government made available public property, not confiscated from its citizens, to those citizens who could benefit from it and were willing and able to improve the land and bring forth its produce to augment the production of the nation. The government did not retain ownership of the land, but turned over ownership to the private citizen after the citizen had earned it and, in the process, proven himself suited and worthy to own it, benefiting the nation in the process. Thus, whereas through an income tax the government confiscated private property, through homesteading the government created private property by distributing parcels of the public domain to those who earned them. And, after all, was not the United States of America a nation of people in a geographic area with a system of government devised by that people: “We the people of the United States of America.” The land did not belong to the government: it belonged to the nation, a nation of people. The representative government of that nation, that “government of the people, by the people, for the people,” merely fulfilled the role of administering the nation’s public land. Since the land of the nation belonged to the people of the nation, and since the land in question did not belong to any particular citizens, why not make it available to the greatest number of citizens or potential citizens (especially those without the capital to purchase it) who would earn ownership of it by improving that land and making a living from it, toward the end of making them productive, propertied citizens? Why not, where it was feasible, open the land to ownership by those citizens who would prove their worthiness to so own through their commitments of time and effort and their achieved improvement of the land? If an applicant could not improve it, could not make it, then he did not earn the property. The property would be open for another to attempt to earn. This process would continue until those who earned ownership of the land were those most suited to inhabiting and making a living from it. It was an investment of the nation in itself, to place upon the land those most suited to bring forth its produce. Was it not in the best interest of the nation to place upon the nation’s land the greatest number of deserving people who could benefit from it, rather than allow the land to be concentrated in monopolies by persons or entities? Did it not give more citizens a stake in the nation, give them more reason to participate as free citizens? And this was not a giveaway. It was a sale, in which those with little or no capital could purchase land through their labor by “proving up.” And it would not contribute to dependence but to independence, as those who earned it were awarded ownership. And it was Republican. Though the roots of homesteading were older than the Republican party and could be traced back to a proposal by Thomas Hart Benton in 1825, and even further back to Thomas Jefferson, who had said, “as few as possible should be without a little parcel of land,” it was the Republicans who had made it law. It had been a plank in the Republican party platform, and Republican Galusha Grow of Pennsylvania had authored the homestead bill that President Lincoln had signed into law in 1862. Lincoln had succinctly said of the policy, “I am in favor of cutting the wild lands into parcels, so that every poor man may have a home.”