© 2012 by P. A. Ritzer

29 August 2012

As I watched one speaker after another intelligently and engagingly put the lie to the Obama and Democratic Party record and talking points, I had to wonder at the PBS team covering the event. First of all, I would have rather heard and seen Janine Turner and Nikki Haley and anyone else I missed when the PBS team deemed that their . . . what? . . . “commentary” and “analysis” should take priority over the contributions of the real players in this one-time event. Among other things, I wondered if the amply seasoned partisan commentators Gwen Ifill, Judy Woodruff, and Mark Shields, and their token conservative–so suited to the role that he writes for the New York Times and was once inspired to prophesy about an inevitable Obama presidency while staring at the crease in Obama’s pants–David Brooks still made a pretense of objectivity.

Regardless, I thought back to an earlier time when I was glad of PBS Republican Convention coverage. It was 1984, and I had finally landed on PBS after hurriedly clicking through the four available channels. Why the rush? Well, because I had noticed that, off in the distance behind John Chancellor droning on to Tom Brokaw, it appeared that Jack Kemp was speaking. No, the networks would not talk over one of the most dynamic and popular Republicans of the day. But, sure enough, when I landed on PBS, there was Kemp. But they would not do that to Jeane Kirkpatrick, the keynote. Sure they would, and at least John and Tom did. Again, I found her on PBS. So, two of the brightest stars of the night, including a brilliant woman who was at the time still a Democrat who would switch to the Republican Party the next year, were kept from the view of the public by tedious liberal commentary. I remember that Paul Harvey–this was still a few years before Rush Limbaugh burst onto the scene and signaled the beginning of the end of the liberal media monopoly, for now–the next day mentioned this abuse of power by the networks and how he would tune to PBS from that time on for coverage of the Republican Convention.

So, I did just that, as well. And during a later campaign, when MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour was the only news program that, despite its liberal bias, would at least bring on guests representing the opposing point of view, I watched their campaign coverage. I remember the glowing backgrounder report on the Democratic Party, stretching well past Martin Van Buren and Andrew Jackson and the Albany-Richmond Axis all the way back to Thomas Jefferson. No mention of slavery, the Dred Scott Decision, the Ku Klux Klan, lynching, the black codes, disfranchisement, Jim Crow, opposition to women’s suffrage. Huh. All right. Well, anyway, I looked forward to the backgrounder on the Republican Party. I believe it was Judy Woodruff who delivered it. As I remember, it started out with how “the modern Republican Party” started with Richard Nixon. What? Not conceived as a reaction to the Kansas-Nebraska Act and its extension of slavery? No Ripon? No Abraham Lincoln? No Emancipation Proclamation? No Frederick Douglass? No Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments? No civil rights laws? No Ulysses S. Grant? No Susan B. Anthony, women’s suffrage, and the Nineteenth Amendment? No Theodore Roosevelt? No Calvin Coolidge? No Dwight D. Eisenhower? No century-long battle against the Democrats to secure civil rights for African-Americans? No, it was Richard Nixon. The “modern” Republican Party started with the most discredited, rightly or wrongly, Republican president in history. How convenient.

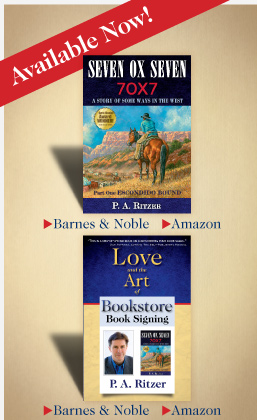

But people are beginning to know better today. The new media is shredding the monopoly of the liberal media, though many–including the Republican establishment–have not yet fully realized it. And thus people have access to sources that belie what was spoon-fed to the public by the old media. And the media did look old on that PBS panel. Nevertheless, they still try, and feisty old Mark Shields thought he had really got one of the guests when he pointed out that the Morrill Act and the Homestead Act, both first passed in 1862, were Republican “government programs.” Yes, but these were not liberal Democratic programs like those of the New Deal and the Great Society designed to create dependence on an ever-expanding government. To illustrate my point, I refer to the following excerpt about the Homestead Act from Seven Ox Seven, Part One: Escondido Bound, pp. 55-56:

In the case of homesteading, the government made available public property, not confiscated from its citizens, to those citizens who could benefit from it and were willing and able to improve the land and bring forth its produce to augment the production of the nation. The government did not retain ownership of the land, but turned over ownership to the private citizen after the citizen had earned it and, in the process, proven himself suited and worthy to own it, benefiting the nation in the process. Thus, whereas through an income tax the government confiscated private property, through homesteading the government created private property by distributing parcels of the public domain to those who earned them.

And, after all, was not the United States of America a nation of people in a geographic area with a system of government devised by that people: “We the people of the United States of America.” The land did not belong to the government: it belonged to the nation, a nation of people. The representative government of that nation, that “government of the people, by the people, for the people,” merely fulfilled the role of administering the nation’s public land. Since the land of the nation belonged to the people of the nation, and since the land in question did not belong to any particular citizens, why not make it available to the greatest number of citizens or potential citizens (especially those without the capital to purchase it) who would earn ownership of it by improving that land and making a living from it, toward the end of making them productive, propertied citizens? Why not, where it was feasible, open the land to ownership by those citizens who would prove their worthiness to so own through their commitments of time and effort and their achieved improvement of the land? If an applicant could not improve it, could not make it, then he did not earn the property. The property would be open for another to attempt to earn. This process would continue until those who earned ownership of the land were those most suited to inhabiting and making a living from it. It was an investment of the nation in itself, to place upon the land those most suited to bring forth its produce.

Was it not in the best interest of the nation to place upon the nation’s land the greatest number of deserving people who could benefit from it, rather than allow the land to be concentrated in monopolies by persons or entities? Did it not give more citizens a stake in the nation, give them more reason to participate as free citizens? And this was not a giveaway. It was a sale, in which those with little or no capital could purchase land through their labor by “proving up.” And it would not contribute to dependence but to independence, as those who earned it were awarded ownership. And it was Republican. Though the roots of homesteading were older than the Republican party and could be traced back to a proposal by Thomas Hart Benton in 1825, and even further back to Thomas Jefferson, who had said, “as few as possible should be without a little parcel of land,” it was the Republicans who had made it law. It had been a plank in the Republican party platform, and Republican Galusha Grow of Pennsylvania had authored the homestead bill that President Lincoln had signed into law in 1862. Lincoln had succinctly said of the policy, “I am in favor of cutting the wild lands into parcels, so that every poor man may have a home.”

The Republican Convention and PBS

© 2012 by P. A. Ritzer

29 August 2012

As I watched one speaker after another intelligently and engagingly put the lie to the Obama and Democratic Party record and talking points, I had to wonder at the PBS team covering the event. First of all, I would have rather heard and seen Janine Turner and Nikki Haley and anyone else I missed when the PBS team deemed that their . . . what? . . . “commentary” and “analysis” should take priority over the contributions of the real players in this one-time event. Among other things, I wondered if the amply seasoned partisan commentators Gwen Ifill, Judy Woodruff, and Mark Shields, and their token conservative–so suited to the role that he writes for the New York Times and was once inspired to prophesy about an inevitable Obama presidency while staring at the crease in Obama’s pants–David Brooks still made a pretense of objectivity.

Regardless, I thought back to an earlier time when I was glad of PBS Republican Convention coverage. It was 1984, and I had finally landed on PBS after hurriedly clicking through the four available channels. Why the rush? Well, because I had noticed that, off in the distance behind John Chancellor droning on to Tom Brokaw, it appeared that Jack Kemp was speaking. No, the networks would not talk over one of the most dynamic and popular Republicans of the day. But, sure enough, when I landed on PBS, there was Kemp. But they would not do that to Jeane Kirkpatrick, the keynote. Sure they would, and at least John and Tom did. Again, I found her on PBS. So, two of the brightest stars of the night, including a brilliant woman who was at the time still a Democrat who would switch to the Republican Party the next year, were kept from the view of the public by tedious liberal commentary. I remember that Paul Harvey–this was still a few years before Rush Limbaugh burst onto the scene and signaled the beginning of the end of the liberal media monopoly, for now–the next day mentioned this abuse of power by the networks and how he would tune to PBS from that time on for coverage of the Republican Convention.

So, I did just that, as well. And during a later campaign, when MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour was the only news program that, despite its liberal bias, would at least bring on guests representing the opposing point of view, I watched their campaign coverage. I remember the glowing backgrounder report on the Democratic Party, stretching well past Martin Van Buren and Andrew Jackson and the Albany-Richmond Axis all the way back to Thomas Jefferson. No mention of slavery, the Dred Scott Decision, the Ku Klux Klan, lynching, the black codes, disfranchisement, Jim Crow, opposition to women’s suffrage. Huh. All right. Well, anyway, I looked forward to the backgrounder on the Republican Party. I believe it was Judy Woodruff who delivered it. As I remember, it started out with how “the modern Republican Party” started with Richard Nixon. What? Not conceived as a reaction to the Kansas-Nebraska Act and its extension of slavery? No Ripon? No Abraham Lincoln? No Emancipation Proclamation? No Frederick Douglass? No Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments? No civil rights laws? No Ulysses S. Grant? No Susan B. Anthony, women’s suffrage, and the Nineteenth Amendment? No Theodore Roosevelt? No Calvin Coolidge? No Dwight D. Eisenhower? No century-long battle against the Democrats to secure civil rights for African-Americans? No, it was Richard Nixon. The “modern” Republican Party started with the most discredited, rightly or wrongly, Republican president in history. How convenient.

But people are beginning to know better today. The new media is shredding the monopoly of the liberal media, though many–including the Republican establishment–have not yet fully realized it. And thus people have access to sources that belie what was spoon-fed to the public by the old media. And the media did look old on that PBS panel. Nevertheless, they still try, and feisty old Mark Shields thought he had really got one of the guests when he pointed out that the Morrill Act and the Homestead Act, both first passed in 1862, were Republican “government programs.” Yes, but these were not liberal Democratic programs like those of the New Deal and the Great Society designed to create dependence on an ever-expanding government. To illustrate my point, I refer to the following excerpt about the Homestead Act from Seven Ox Seven, Part One: Escondido Bound, pp. 55-56:

In the case of homesteading, the government made available public property, not confiscated from its citizens, to those citizens who could benefit from it and were willing and able to improve the land and bring forth its produce to augment the production of the nation. The government did not retain ownership of the land, but turned over ownership to the private citizen after the citizen had earned it and, in the process, proven himself suited and worthy to own it, benefiting the nation in the process. Thus, whereas through an income tax the government confiscated private property, through homesteading the government created private property by distributing parcels of the public domain to those who earned them. And, after all, was not the United States of America a nation of people in a geographic area with a system of government devised by that people: “We the people of the United States of America.” The land did not belong to the government: it belonged to the nation, a nation of people. The representative government of that nation, that “government of the people, by the people, for the people,” merely fulfilled the role of administering the nation’s public land. Since the land of the nation belonged to the people of the nation, and since the land in question did not belong to any particular citizens, why not make it available to the greatest number of citizens or potential citizens (especially those without the capital to purchase it) who would earn ownership of it by improving that land and making a living from it, toward the end of making them productive, propertied citizens? Why not, where it was feasible, open the land to ownership by those citizens who would prove their worthiness to so own through their commitments of time and effort and their achieved improvement of the land? If an applicant could not improve it, could not make it, then he did not earn the property. The property would be open for another to attempt to earn. This process would continue until those who earned ownership of the land were those most suited to inhabiting and making a living from it. It was an investment of the nation in itself, to place upon the land those most suited to bring forth its produce. Was it not in the best interest of the nation to place upon the nation’s land the greatest number of deserving people who could benefit from it, rather than allow the land to be concentrated in monopolies by persons or entities? Did it not give more citizens a stake in the nation, give them more reason to participate as free citizens? And this was not a giveaway. It was a sale, in which those with little or no capital could purchase land through their labor by “proving up.” And it would not contribute to dependence but to independence, as those who earned it were awarded ownership. And it was Republican. Though the roots of homesteading were older than the Republican party and could be traced back to a proposal by Thomas Hart Benton in 1825, and even further back to Thomas Jefferson, who had said, “as few as possible should be without a little parcel of land,” it was the Republicans who had made it law. It had been a plank in the Republican party platform, and Republican Galusha Grow of Pennsylvania had authored the homestead bill that President Lincoln had signed into law in 1862. Lincoln had succinctly said of the policy, “I am in favor of cutting the wild lands into parcels, so that every poor man may have a home.”