15 March 2012

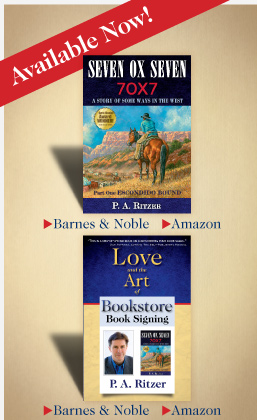

From Seven Ox Seven, Part One: Escondido Bound, the third of three excerpts from pages 219-228.

Copyright © 2007 by P. A. Ritzer

Like the lawless, the semi-lawful did not respect the laws of the state, though not to the point of disregarding them altogether as the lawless would. Like the lawful, the semi-lawful relinquished their responsibility to the state, though not in the passive way of the lawful, but rather in an aggressive way. The lawful just went along with what they were doing for their own benefit, without regard for their consciences, their free wills, their responsibilities, their places within the human communion, and their roles of stewards of the earth, until the state passed a law to stop them. The semi-lawful also went along with what they were doing for their own benefit, without regard for their consciences, their free wills, their responsibilities, their places within the human communion, and their roles of stewards of the earth, until the state passed a law to stop them, but the semi-lawful would go further.

The semi-lawful would then defy the law, often enough within the bounds of the law, by challenging the law, by pushing it to its limits, by finding and using every loophole in the law, by defying the spirit of the law to get around the law through legal trivialities, which would require more laws to be passed to close the loopholes and address the trivialities, which would serve to further restrict the freedom of the people. Or sometimes the semi-lawful would even break the law, where the chances of their being held to account were slight. The semi-lawful would not just submit to letting the state legislate their morality, thereby relinquishing their responsibility to the state, as would the lawful, but they would actually go so far as to ascribe to the state the role of conscience, and, even then, rather than obey that surrogate conscience, they would fight it, stretching it, in any way, to allow them license, which they would mistake for freedom. Even then, the semi-lawful would blame any moral failings on the imperfections in the laws of the state, which had borne their steady attack. This was not to be confused with the conscientious who might responsibly oppose a law and seek to have it changed because it contradicts their informed consciences. Instead it was the semi-lawful rejecting the conscience and then ascribing the role of conscience to the state and then opposing that surrogate conscience to enhance their license.

Interestingly enough, as soon as these semi-lawful would see a competitor (which to one of the semi-lawful was almost every other person) reaping a better benefit than they were from an area of endeavor where there was no law, or there was a loophole in the law, or there was a law that favored the competitor, the semi-lawful would demand a law to curb the success of that competitor, even if the law restricted the license of the semi-lawful. Once such a law was passed, the semi-lawful would go about finding a way around that law, until another competitor did so better than they, at which time the semi-lawful would again demand another law.

These semi-lawful, like defiant children against their parents, could grow very proud of themselves as they battled against their surrogate consciences and their ubiquitous competitors and made their little victories here and there. They could believe themselves quite superior to all others because of how well they played the game they believed life to be.

Tom thought about that and wondered how superior the semi-lawful would consider themselves if there were no lawful or conscientious or even other semi-lawful over whom they could triumph. Put them in among the lawless only, among those who had a more honest disregard for the law, and see how well the semi-lawful would fare. There would be the real game; there would be the fair match, with all law stripped away and all participants equally unrestrained. How long would the semi-lawful remain superior without the law they so abused and without the conscientious and the lawful—constrained by conscience, law, or both—upon whom the semi-lawful could prey?

Regardless, the irony was that a good many of those to whom the semi-lawful felt so superior, especially the conscientious, were not only not playing the game, but they were not even in the game. A good many of those over whom the semi-lawful believed they were triumphing, did not even know there was a game. These, especially the conscientious, would have been surprised to know that the semi-lawful lived life as a contest against imaginary competitors and a surrogate conscience, rather than as the wholly gratuitous gift of existence, the unimaginable opportunity to be in the vast universe of time and space, the preciously limited opportunity to seek perfection rather than trivial victories over self-created foes.

The conscientious, to varying degrees, knew life as this gift, this opportunity. They knew the importance of forming their consciences and being ruled by those consciences attuned to “the laws of nature and of nature’s God.” They knew that a free society demanded that its citizens be disciplined, that they be virtuous, that they be responsible. They knew that if the citizens instead rejected virtue or did not seek it, and if they did not form their consciences, and if they substituted for the conscience some construct of man, then they set themselves up for anarchy or for tyranny by a power-hungry elite, often enough composed of the semi-lawful.

In considering these examples of the conscientious, the lawful, the semi-lawful, and the lawless, Tom considered the problem of a free society where not all the citizens valued virtue, where not all were conscientious. As a result, Tom concluded that the best system of government on earth was a representative government like that of the republic of the United States of America, which he loved. And he believed that such a representative government, founded by the conscientious, was best because it allowed for the possibility of having a government made up of the conscientious, limited in terms so as not to corrupt their conscientiousness. And he believed that, with a republic so founded and sustained, there was a chance that the government would respect and sustain the free will of its citizens, and, at the same time, protect, from abuses of free will, those citizens’ God-given rights.

Such was the ideal, but Tom had just been considering the categories of the conscientious, the lawful, the semi-lawful, and the lawless, and he knew that the ideal was far from realization. For one thing, the representatives were elected by the citizens, and there was no guarantee that the citizens would elect only the conscientious. Instead, there was a good probability that they would not elect only the conscientious, and plenty of history to support that probability. For another thing, even if only the conscientious were elected, they would only be conscientious to the degree that they would form and obey their consciences. Experience suggested that this formation and obedience would not be perfect. One only need look at the founding of the great United States to see that its conscientious founders allowed it to be conceived within the context of its original sin of slavery, a context radically contrary to the exalted principles instrumental in its conception.

Ah, there it was, the nation’s original sin, but that was only a relatively recent manifestation of the root of the problem. The root of the problem lay in the original sin of the human race that left man with a wounded human nature, which, though it was not totally corrupted, was thereafter inclined to sin, the result of proud opposition and disobedience, in a garden, that led to a tree of forbidden knowledge and deprived man of access to the tree of life. Therein lay the font of destruction for any free society. And that destruction was inevitable but for one quiet though superabundant hope, the result of humble submission and obedience, in another garden, that led to a new tree of knowledge that became the tree of life.

Therein lay the problem and the solution, Tom thought. And as he rode through the stench and the flies and the carcasses and the bones and the hides and the hunters and the booms of Sharps rifles, Tom thought of how much better the world could be if people accepted the truths presented in figurative language in the story of the first garden and then accepted the Truth made accessible because of the submission in the second garden. Such was his hope, and such was his prayer, as the Stuart-Schurtz party progressed along the Mackenzie Trail, drawing ever nearer the escarpment of the Llano Estacado.