15 March 2012

From Seven Ox Seven, Part One: Escondido Bound, the third of three excerpts from pages 219-228.

Copyright © 2007 by P. A. Ritzer

Like the lawless, the semi-lawful did not respect the laws of the state, though not to the point of disregarding them altogether as the lawless would. Like the lawful, the semi-lawful relinquished their responsibility to the state, though not in the passive way of the lawful, but rather in an aggressive way. The lawful just went along with what they were doing for their own benefit, without regard for their consciences, their free wills, their responsibilities, their places within the human communion, and their roles of stewards of the earth, until the state passed a law to stop them. The semi-lawful also went along with what they were doing for their own benefit, without regard for their consciences, their free wills, their responsibilities, their places within the human communion, and their roles of stewards of the earth, until the state passed a law to stop them, but the semi-lawful would go further.

The semi-lawful would then defy the law, often enough within the bounds of the law, by challenging the law, by pushing it to its limits, by finding and using every loophole in the law, by defying the spirit of the law to get around the law through legal trivialities, which would require more laws to be passed to close the loopholes and address the trivialities, which would serve to further restrict the freedom of the people. Or sometimes the semi-lawful would even break the law, where the chances of their being held to account were slight. The semi-lawful would not just submit to letting the state legislate their morality, thereby relinquishing their responsibility to the state, as would the lawful, but they would actually go so far as to ascribe to the state the role of conscience, and, even then, rather than obey that surrogate conscience, they would fight it, stretching it, in any way, to allow them license, which they would mistake for freedom. Even then, the semi-lawful would blame any moral failings on the imperfections in the laws of the state, which had borne their steady attack. This was not to be confused with the conscientious who might responsibly oppose a law and seek to have it changed because it contradicts their informed consciences. Instead it was the semi-lawful rejecting the conscience and then ascribing the role of conscience to the state and then opposing that surrogate conscience to enhance their license.

Interestingly enough, as soon as these semi-lawful would see a competitor (which to one of the semi-lawful was almost every other person) reaping a better benefit than they were from an area of endeavor where there was no law, or there was a loophole in the law, or there was a law that favored the competitor, the semi-lawful would demand a law to curb the success of that competitor, even if the law restricted the license of the semi-lawful. Once such a law was passed, the semi-lawful would go about finding a way around that law, until another competitor did so better than they, at which time the semi-lawful would again demand another law.

These semi-lawful, like defiant children against their parents, could grow very proud of themselves as they battled against their surrogate consciences and their ubiquitous competitors and made their little victories here and there. They could believe themselves quite superior to all others because of how well they played the game they believed life to be.

Tom thought about that and wondered how superior the semi-lawful would consider themselves if there were no lawful or conscientious or even other semi-lawful over whom they could triumph. Put them in among the lawless only, among those who had a more honest disregard for the law, and see how well the semi-lawful would fare. There would be the real game; there would be the fair match, with all law stripped away and all participants equally unrestrained. How long would the semi-lawful remain superior without the law they so abused and without the conscientious and the lawful—constrained by conscience, law, or both—upon whom the semi-lawful could prey?

Regardless, the irony was that a good many of those to whom the semi-lawful felt so superior, especially the conscientious, were not only not playing the game, but they were not even in the game. A good many of those over whom the semi-lawful believed they were triumphing, did not even know there was a game. These, especially the conscientious, would have been surprised to know that the semi-lawful lived life as a contest against imaginary competitors and a surrogate conscience, rather than as the wholly gratuitous gift of existence, the unimaginable opportunity to be in the vast universe of time and space, the preciously limited opportunity to seek perfection rather than trivial victories over self-created foes.

The conscientious, to varying degrees, knew life as this gift, this opportunity. They knew the importance of forming their consciences and being ruled by those consciences attuned to “the laws of nature and of nature’s God.” They knew that a free society demanded that its citizens be disciplined, that they be virtuous, that they be responsible. They knew that if the citizens instead rejected virtue or did not seek it, and if they did not form their consciences, and if they substituted for the conscience some construct of man, then they set themselves up for anarchy or for tyranny by a power-hungry elite, often enough composed of the semi-lawful.

In considering these examples of the conscientious, the lawful, the semi-lawful, and the lawless, Tom considered the problem of a free society where not all the citizens valued virtue, where not all were conscientious. As a result, Tom concluded that the best system of government on earth was a representative government like that of the republic of the United States of America, which he loved. And he believed that such a representative government, founded by the conscientious, was best because it allowed for the possibility of having a government made up of the conscientious, limited in terms so as not to corrupt their conscientiousness. And he believed that, with a republic so founded and sustained, there was a chance that the government would respect and sustain the free will of its citizens, and, at the same time, protect, from abuses of free will, those citizens’ God-given rights.

Such was the ideal, but Tom had just been considering the categories of the conscientious, the lawful, the semi-lawful, and the lawless, and he knew that the ideal was far from realization. For one thing, the representatives were elected by the citizens, and there was no guarantee that the citizens would elect only the conscientious. Instead, there was a good probability that they would not elect only the conscientious, and plenty of history to support that probability. For another thing, even if only the conscientious were elected, they would only be conscientious to the degree that they would form and obey their consciences. Experience suggested that this formation and obedience would not be perfect. One only need look at the founding of the great United States to see that its conscientious founders allowed it to be conceived within the context of its original sin of slavery, a context radically contrary to the exalted principles instrumental in its conception.

Ah, there it was, the nation’s original sin, but that was only a relatively recent manifestation of the root of the problem. The root of the problem lay in the original sin of the human race that left man with a wounded human nature, which, though it was not totally corrupted, was thereafter inclined to sin, the result of proud opposition and disobedience, in a garden, that led to a tree of forbidden knowledge and deprived man of access to the tree of life. Therein lay the font of destruction for any free society. And that destruction was inevitable but for one quiet though superabundant hope, the result of humble submission and obedience, in another garden, that led to a new tree of knowledge that became the tree of life.

Therein lay the problem and the solution, Tom thought. And as he rode through the stench and the flies and the carcasses and the bones and the hides and the hunters and the booms of Sharps rifles, Tom thought of how much better the world could be if people accepted the truths presented in figurative language in the story of the first garden and then accepted the Truth made accessible because of the submission in the second garden. Such was his hope, and such was his prayer, as the Stuart-Schurtz party progressed along the Mackenzie Trail, drawing ever nearer the escarpment of the Llano Estacado.

The Republican Convention and PBS

© 2012 by P. A. Ritzer

29 August 2012

As I watched one speaker after another intelligently and engagingly put the lie to the Obama and Democratic Party record and talking points, I had to wonder at the PBS team covering the event. First of all, I would have rather heard and seen Janine Turner and Nikki Haley and anyone else I missed when the PBS team deemed that their . . . what? . . . “commentary” and “analysis” should take priority over the contributions of the real players in this one-time event. Among other things, I wondered if the amply seasoned partisan commentators Gwen Ifill, Judy Woodruff, and Mark Shields, and their token conservative–so suited to the role that he writes for the New York Times and was once inspired to prophesy about an inevitable Obama presidency while staring at the crease in Obama’s pants–David Brooks still made a pretense of objectivity.

Regardless, I thought back to an earlier time when I was glad of PBS Republican Convention coverage. It was 1984, and I had finally landed on PBS after hurriedly clicking through the four available channels. Why the rush? Well, because I had noticed that, off in the distance behind John Chancellor droning on to Tom Brokaw, it appeared that Jack Kemp was speaking. No, the networks would not talk over one of the most dynamic and popular Republicans of the day. But, sure enough, when I landed on PBS, there was Kemp. But they would not do that to Jeane Kirkpatrick, the keynote. Sure they would, and at least John and Tom did. Again, I found her on PBS. So, two of the brightest stars of the night, including a brilliant woman who was at the time still a Democrat who would switch to the Republican Party the next year, were kept from the view of the public by tedious liberal commentary. I remember that Paul Harvey–this was still a few years before Rush Limbaugh burst onto the scene and signaled the beginning of the end of the liberal media monopoly, for now–the next day mentioned this abuse of power by the networks and how he would tune to PBS from that time on for coverage of the Republican Convention.

So, I did just that, as well. And during a later campaign, when MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour was the only news program that, despite its liberal bias, would at least bring on guests representing the opposing point of view, I watched their campaign coverage. I remember the glowing backgrounder report on the Democratic Party, stretching well past Martin Van Buren and Andrew Jackson and the Albany-Richmond Axis all the way back to Thomas Jefferson. No mention of slavery, the Dred Scott Decision, the Ku Klux Klan, lynching, the black codes, disfranchisement, Jim Crow, opposition to women’s suffrage. Huh. All right. Well, anyway, I looked forward to the backgrounder on the Republican Party. I believe it was Judy Woodruff who delivered it. As I remember, it started out with how “the modern Republican Party” started with Richard Nixon. What? Not conceived as a reaction to the Kansas-Nebraska Act and its extension of slavery? No Ripon? No Abraham Lincoln? No Emancipation Proclamation? No Frederick Douglass? No Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments? No civil rights laws? No Ulysses S. Grant? No Susan B. Anthony, women’s suffrage, and the Nineteenth Amendment? No Theodore Roosevelt? No Calvin Coolidge? No Dwight D. Eisenhower? No century-long battle against the Democrats to secure civil rights for African-Americans? No, it was Richard Nixon. The “modern” Republican Party started with the most discredited, rightly or wrongly, Republican president in history. How convenient.

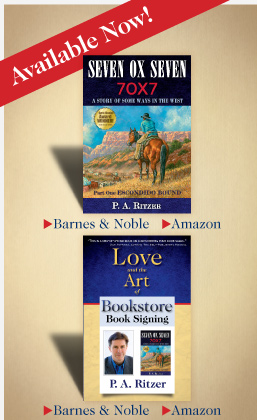

But people are beginning to know better today. The new media is shredding the monopoly of the liberal media, though many–including the Republican establishment–have not yet fully realized it. And thus people have access to sources that belie what was spoon-fed to the public by the old media. And the media did look old on that PBS panel. Nevertheless, they still try, and feisty old Mark Shields thought he had really got one of the guests when he pointed out that the Morrill Act and the Homestead Act, both first passed in 1862, were Republican “government programs.” Yes, but these were not liberal Democratic programs like those of the New Deal and the Great Society designed to create dependence on an ever-expanding government. To illustrate my point, I refer to the following excerpt about the Homestead Act from Seven Ox Seven, Part One: Escondido Bound, pp. 55-56:

In the case of homesteading, the government made available public property, not confiscated from its citizens, to those citizens who could benefit from it and were willing and able to improve the land and bring forth its produce to augment the production of the nation. The government did not retain ownership of the land, but turned over ownership to the private citizen after the citizen had earned it and, in the process, proven himself suited and worthy to own it, benefiting the nation in the process. Thus, whereas through an income tax the government confiscated private property, through homesteading the government created private property by distributing parcels of the public domain to those who earned them. And, after all, was not the United States of America a nation of people in a geographic area with a system of government devised by that people: “We the people of the United States of America.” The land did not belong to the government: it belonged to the nation, a nation of people. The representative government of that nation, that “government of the people, by the people, for the people,” merely fulfilled the role of administering the nation’s public land. Since the land of the nation belonged to the people of the nation, and since the land in question did not belong to any particular citizens, why not make it available to the greatest number of citizens or potential citizens (especially those without the capital to purchase it) who would earn ownership of it by improving that land and making a living from it, toward the end of making them productive, propertied citizens? Why not, where it was feasible, open the land to ownership by those citizens who would prove their worthiness to so own through their commitments of time and effort and their achieved improvement of the land? If an applicant could not improve it, could not make it, then he did not earn the property. The property would be open for another to attempt to earn. This process would continue until those who earned ownership of the land were those most suited to inhabiting and making a living from it. It was an investment of the nation in itself, to place upon the land those most suited to bring forth its produce. Was it not in the best interest of the nation to place upon the nation’s land the greatest number of deserving people who could benefit from it, rather than allow the land to be concentrated in monopolies by persons or entities? Did it not give more citizens a stake in the nation, give them more reason to participate as free citizens? And this was not a giveaway. It was a sale, in which those with little or no capital could purchase land through their labor by “proving up.” And it would not contribute to dependence but to independence, as those who earned it were awarded ownership. And it was Republican. Though the roots of homesteading were older than the Republican party and could be traced back to a proposal by Thomas Hart Benton in 1825, and even further back to Thomas Jefferson, who had said, “as few as possible should be without a little parcel of land,” it was the Republicans who had made it law. It had been a plank in the Republican party platform, and Republican Galusha Grow of Pennsylvania had authored the homestead bill that President Lincoln had signed into law in 1862. Lincoln had succinctly said of the policy, “I am in favor of cutting the wild lands into parcels, so that every poor man may have a home.”