1 February 2012

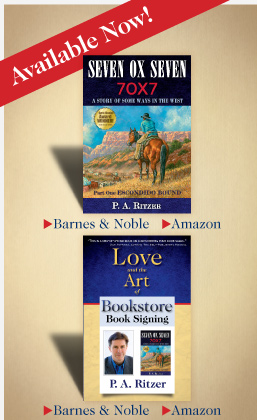

From Seven Ox Seven, Part One: Escondido Bound, the first of three excerpts from pages 219-228.

Copyright © 2007 by P. A. Ritzer

Tom, for his part, still reflected as he rode along through the region in the dust of the trailing herd. One thing of which he was sure was that the slaughter was wrong. The hunting of the buffalo was not wrong. The skinning of the buffalo was not wrong. The sale and use of those skins for clothing, industry, or any other legitimate use was not wrong. Even the reduction of the vast buffalo herds to make way for other uses of the land was not necessarily wrong. What was wrong was the greed behind it all and what that greed had wrought.

What that greed had wrought was the waste of untold tons of meat (and even the waste of many of the hides for which the animals had been killed, due to hasty skinning, curing, or both). It had wrought a slaughter that, if it continued apace (and there was every reason to believe that it would), was sure to wipe out the species without due consideration of all the ramifications of that extermination. It had wrought further enmity between whites and the Plains Indians and the further reduction of those peoples to a pathetic dependency.

It had wrought all of those things and more, Tom could see. And yet, as disturbing as all that was, there was another work of that greed that encompassed all the rest, and that was the work of perverting freedom into license. Tom believed that such a large-scale perversion of freedom was detrimental to, and indicative of, the relative health of a nation, especially of one that had been founded with the security of the inalienable right of liberty as one of its central tenets and had recently fought a bloody civil war to preserve itself and abolish the singularly most glaring and festering contradiction to that tenet. Where freedom degenerates into license, he mused, man has already relinquished the mastery of himself to his passions, and it only remains to be seen who or what will succeed his passions as his master. In such circumstances, a free society is very much in danger.

There is no true freedom without responsibility. In light of that truth, Tom thought of some of the buffalo hunters he had met along the trail and before. Despite the common characterization of the buffalo hunter, some of these hunters were respectable people, some of them whole families, and many of them regretted the wasteful slaughter of the buffalo, actually lamented the part they were playing in it. Yet, they licentiously continued in it, killing as many as they could as quickly as they could, before there were no more to kill, because they were desperate to get as much as they could out of the slaughter, desperate to secure their part of the fortune that the buffalo hides represented. Had a law been passed to stop the slaughter and preserve the breed (and there were several attempts at such legislation throughout the 1870s), they would have gladly obeyed it and been glad for it, and yet, as long as there was no law, they would continue to play their part in the slaughter up to the very extinction of the animal.

Due to greed, and the pride behind it, these hunters were willing to reject their God-given stewardship of the earth. They were willing to relinquish their own judgment of what was right and wrong, as well as their freedom to act upon it, because they wanted to get all that they could get, and they did not want to fall behind anyone else who might be profiting from the same motivation and the same refusal to govern himself according to right and wrong. Tom thought about how that tendency was not so uncommon, how that tendency was, indeed, universal. Still, there were individuals, call them the conscientious, who, through prayer, reflection, or both, came to know such tendencies in themselves and to see the evil in those tendencies and, with the help of grace, to overcome or check those tendencies, to greater or lesser degrees. In doing so, the conscientious were forming their consciences, and in doing so according to objective truths, these individuals were subjecting themselves to “the laws of nature and of nature’s God,” cited in the Declaration of Independence, a subjection without which a free society must degenerate into anarchy or tyranny or the ugliest amalgamations of both.

A free society depends upon the will of the individuals in that society to take personal responsibility for their freedom, to govern themselves according to objective truths of right and wrong, Tom reasoned. When the individuals of a free society refuse or even just neglect to take responsibility for their freedom, when they refuse or neglect to form their consciences and to be ruled by those consciences attuned to “the laws of nature and of nature’s God,” then those individuals choose license over freedom, and they give in to a progression toward disorder or toward being ruled by something other than the self guided by conscience.

Tom saw just such a progression in this matter of the buffalo. He considered those hunters, not the lawless element of that occupation, but those respectable ones, call them the lawful, as they were willing to submit to the laws of the state. He considered those lawful, who would willingly and gladly stop the slaughter, and even feel relieved to do so, if only the state would enact a law requiring it. He considered how those lawful were passing on the responsibility for their actions to the state, and with it, they were passing on their freedom, their right of liberty, their right of self-government. He thought of all that it had cost in human sacrifice to establish and preserve a nation that had been founded to protect freedom and other human rights. Then he thought of how such shirking of responsibility and freedom and relinquishing of rights were unworthy of that sacrifice, and of how it would be better to have one’s freedom and rights usurped rather than to have them so carelessly discarded.

Interestingly enough, even the lawless element of the buffalo hunters (those apparently most opposed to being ruled by others), though they might refuse or neglect to discern the wrongness of the slaughter that the lawful had discerned, and, in fact, because they refused or neglected to do so, they too were passing on their freedom to the state, because they would not even accept responsibility for their freedom to discern. These lawless too were giving the state greater power with which to rule over them, even if they intended to defy that power. Both kinds of men, those who had some respect for the law and those who did not, were willing to let their freedom be overwhelmed by the dictates of the state.

(continued in Part Two)