15 March 2012

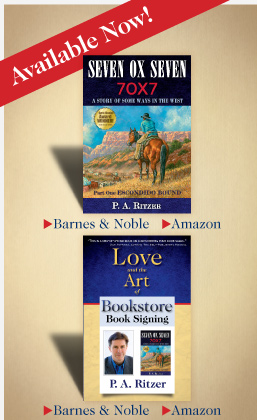

From Seven Ox Seven, Part One: Escondido Bound, the third of three excerpts from pages 219-228.

Copyright © 2007 by P. A. Ritzer

Like the lawless, the semi-lawful did not respect the laws of the state, though not to the point of disregarding them altogether as the lawless would. Like the lawful, the semi-lawful relinquished their responsibility to the state, though not in the passive way of the lawful, but rather in an aggressive way. The lawful just went along with what they were doing for their own benefit, without regard for their consciences, their free wills, their responsibilities, their places within the human communion, and their roles of stewards of the earth, until the state passed a law to stop them. The semi-lawful also went along with what they were doing for their own benefit, without regard for their consciences, their free wills, their responsibilities, their places within the human communion, and their roles of stewards of the earth, until the state passed a law to stop them, but the semi-lawful would go further.

The semi-lawful would then defy the law, often enough within the bounds of the law, by challenging the law, by pushing it to its limits, by finding and using every loophole in the law, by defying the spirit of the law to get around the law through legal trivialities, which would require more laws to be passed to close the loopholes and address the trivialities, which would serve to further restrict the freedom of the people. Or sometimes the semi-lawful would even break the law, where the chances of their being held to account were slight. The semi-lawful would not just submit to letting the state legislate their morality, thereby relinquishing their responsibility to the state, as would the lawful, but they would actually go so far as to ascribe to the state the role of conscience, and, even then, rather than obey that surrogate conscience, they would fight it, stretching it, in any way, to allow them license, which they would mistake for freedom. Even then, the semi-lawful would blame any moral failings on the imperfections in the laws of the state, which had borne their steady attack. This was not to be confused with the conscientious who might responsibly oppose a law and seek to have it changed because it contradicts their informed consciences. Instead it was the semi-lawful rejecting the conscience and then ascribing the role of conscience to the state and then opposing that surrogate conscience to enhance their license.

Interestingly enough, as soon as these semi-lawful would see a competitor (which to one of the semi-lawful was almost every other person) reaping a better benefit than they were from an area of endeavor where there was no law, or there was a loophole in the law, or there was a law that favored the competitor, the semi-lawful would demand a law to curb the success of that competitor, even if the law restricted the license of the semi-lawful. Once such a law was passed, the semi-lawful would go about finding a way around that law, until another competitor did so better than they, at which time the semi-lawful would again demand another law.

These semi-lawful, like defiant children against their parents, could grow very proud of themselves as they battled against their surrogate consciences and their ubiquitous competitors and made their little victories here and there. They could believe themselves quite superior to all others because of how well they played the game they believed life to be.

Tom thought about that and wondered how superior the semi-lawful would consider themselves if there were no lawful or conscientious or even other semi-lawful over whom they could triumph. Put them in among the lawless only, among those who had a more honest disregard for the law, and see how well the semi-lawful would fare. There would be the real game; there would be the fair match, with all law stripped away and all participants equally unrestrained. How long would the semi-lawful remain superior without the law they so abused and without the conscientious and the lawful—constrained by conscience, law, or both—upon whom the semi-lawful could prey?

Regardless, the irony was that a good many of those to whom the semi-lawful felt so superior, especially the conscientious, were not only not playing the game, but they were not even in the game. A good many of those over whom the semi-lawful believed they were triumphing, did not even know there was a game. These, especially the conscientious, would have been surprised to know that the semi-lawful lived life as a contest against imaginary competitors and a surrogate conscience, rather than as the wholly gratuitous gift of existence, the unimaginable opportunity to be in the vast universe of time and space, the preciously limited opportunity to seek perfection rather than trivial victories over self-created foes.

The conscientious, to varying degrees, knew life as this gift, this opportunity. They knew the importance of forming their consciences and being ruled by those consciences attuned to “the laws of nature and of nature’s God.” They knew that a free society demanded that its citizens be disciplined, that they be virtuous, that they be responsible. They knew that if the citizens instead rejected virtue or did not seek it, and if they did not form their consciences, and if they substituted for the conscience some construct of man, then they set themselves up for anarchy or for tyranny by a power-hungry elite, often enough composed of the semi-lawful.

In considering these examples of the conscientious, the lawful, the semi-lawful, and the lawless, Tom considered the problem of a free society where not all the citizens valued virtue, where not all were conscientious. As a result, Tom concluded that the best system of government on earth was a representative government like that of the republic of the United States of America, which he loved. And he believed that such a representative government, founded by the conscientious, was best because it allowed for the possibility of having a government made up of the conscientious, limited in terms so as not to corrupt their conscientiousness. And he believed that, with a republic so founded and sustained, there was a chance that the government would respect and sustain the free will of its citizens, and, at the same time, protect, from abuses of free will, those citizens’ God-given rights.

Such was the ideal, but Tom had just been considering the categories of the conscientious, the lawful, the semi-lawful, and the lawless, and he knew that the ideal was far from realization. For one thing, the representatives were elected by the citizens, and there was no guarantee that the citizens would elect only the conscientious. Instead, there was a good probability that they would not elect only the conscientious, and plenty of history to support that probability. For another thing, even if only the conscientious were elected, they would only be conscientious to the degree that they would form and obey their consciences. Experience suggested that this formation and obedience would not be perfect. One only need look at the founding of the great United States to see that its conscientious founders allowed it to be conceived within the context of its original sin of slavery, a context radically contrary to the exalted principles instrumental in its conception.

Ah, there it was, the nation’s original sin, but that was only a relatively recent manifestation of the root of the problem. The root of the problem lay in the original sin of the human race that left man with a wounded human nature, which, though it was not totally corrupted, was thereafter inclined to sin, the result of proud opposition and disobedience, in a garden, that led to a tree of forbidden knowledge and deprived man of access to the tree of life. Therein lay the font of destruction for any free society. And that destruction was inevitable but for one quiet though superabundant hope, the result of humble submission and obedience, in another garden, that led to a new tree of knowledge that became the tree of life.

Therein lay the problem and the solution, Tom thought. And as he rode through the stench and the flies and the carcasses and the bones and the hides and the hunters and the booms of Sharps rifles, Tom thought of how much better the world could be if people accepted the truths presented in figurative language in the story of the first garden and then accepted the Truth made accessible because of the submission in the second garden. Such was his hope, and such was his prayer, as the Stuart-Schurtz party progressed along the Mackenzie Trail, drawing ever nearer the escarpment of the Llano Estacado.

Revisiting Dr. Seuss In Parenthood (Part One)

5 January 2012

The following commentary first appeared in Saint Austin Review, July/August 2005. It appears here with some revisions. Quotations in quotation marks and block quotes are from the works being considered.

In this election year, we might give special attention to the case of Yertle the Turtle and consider well the growing weight of government and taxation, especially considering the founders’ conviction that it must be a limited government–as established with the Constitution, “deriving [its] just powers from the consent of the governed” (as the Declaration of Independence would have it)–that best secures the “unalienable rights” with which our Creator has endowed us.

Copyright © 2003 by P. A. Ritzer

I remember my brother saying, years ago, that he looked forward to having children of his own, so that he could again watch old Disney movies. I, for my part, in my parenthood, have discovered the joy of revisiting Dr. Seuss and sharing his works, his stories, his words with my children.

This is not my first revisiting. The birth of my nephew and godson in 1990 opened the door for the first revisiting, which went so far as to include sharing with him and his parents a breakfast of green eggs and ham. It was during this first re-acquaintance that I remember declaring that Dr. Seuss was the Shakespeare for children. This declaration, besides being inspired by an adult appreciation for the genius of these works that I had so enjoyed as a child, may also have been an enlightened response to a long-remembered concern, voiced by my parents, and possibly initiated by my teacher, that at second, third, or fourth grade (some grade that was still on the first floor of Sacred Hearts School), perhaps I was too old to be reading Dr. Seuss. My youthful appreciation for these works has since been further vindicated, at least in my eyes, by the discovery that these classics were prescribed for my wife, long before she met me, to alleviate the stress of medical school exams, by a good friend and classmate, with whom she read the works in a stairwell amidst their echoing laughter. The prescriber is now a psychiatrist for both children and adults.

I offer no blanket endorsement or recommendation of the thought and works of Theodor Seuss Geisel. I do not know his thought and have not read all his works, nor have I revisited all his works which I read as a boy. But rather, what I wish to do is to share, as an adult and parent who struggles to live a Christian life in our modern world, an appreciation for the values expressed in at least some of the words, stories, and works of Dr. Seuss.

Certainly, in Green Eggs and Ham the reader is taught a lesson about deciding to dislike foods before one tries them, but does not the persistent Sam eventually wear down the nameless green-eggs-and-ham-hater’s pride- and ignorance-based prejudice, so that he might lead a fuller life with his discovery: “’Say! I like green eggs and ham! I do! I like them, Sam-I-am!’” Thus, the changed fellow can come to the grateful conclusion: “’I do so like green eggs and ham! Thank you! Thank you, Sam-I-am!’”

And, in our culture in which the words nip, tuck, and augmentation have become commonplace, might not the young reader benefit from considering the case of Gertrude McFuzz, a “girl-bird” who “had the smallest plain tail ever was. One droopy-droop feather. That’s all that she had. And, oh! That one feather made Gertrude so sad,” when she compared herself to “a fancy young birdie named Lolla-Lee-Lou,” who “instead of one feather behind, she had two!” This state of affairs leads a jealous Gertrude to one day shout in anger, “‘This just isn’t fair! I have one! She has two! I MUST have a tail just like Lolla-Lee-Lou!'”

Despite the admonition of her wise uncle Doctor Dake, who assures her, “’Your tail is just right for your kind of a bird,’” she throws tantrums, until he tells her of the pills of the pill-berry vine, which will make her tail grow. And although one pill gives her tail another feather, “exactly like Lolla-Lee-Lou,” she decides to “grow a tail better than Lolla-Lee-Lou.” And she does, by gobbling all the pill-berries down. She grows a tail so stupendous that “that bird couldn’t fly! Couldn’t run! Couldn’t walk!”

It takes her uncle and his assistants two weeks to fly Gertrude home. And Dr. Seuss relates:

And how much smarter or wiser might the young reader be after considering the case of Yertle the Turtle, king of the Pond on the Isle of Sala-ma-Sond, where “the turtles had everything turtles might need. And they were all happy. Quite happy indeed.”

So, Yertle begins to build a higher throne on the backs of his subjects, by commanding the turtles to stack themselves up, one on top of the other, beneath him, so that Yertle can see more and exclaim: “’I’m Yertle the Turtle! Oh, marvelous me! For I am the ruler of all that I see!’”

But the burden on the common folks grows to be too much to bear, so that “from below in the great heavy stack, [comes] a groan from that plain little turtle named Mack,” who petitions the king from his distress at the bottom of the stack, “’I know, up on top you are seeing great sights, But down at the bottom we, too, should have rights.’”

By now, though, the power-drunk Yertle has lost all sense of proportion, and after silencing Mack, he begins to call for more turtles that he might build his throne higher than the moon, when:

And from that throne, shaken by the common movement of the lowest subject upon which his corrupt foundation of exploitation is built, falls the mighty Yertle, “that Marvelous he,” into the depths of the mud. And “that was the end of the Turtle King’s rule!” The tyrant is thus deposed, “And the turtles, of course . . . all the turtles are free As turtles and, maybe, all creatures should be.”

(to be continued in Part Two)