1 March 2012

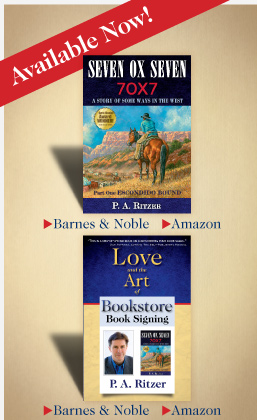

From Seven Ox Seven, Part One: Escondido Bound, the second of three excerpts from pages 219-228.

Copyright © 2007 by P. A. Ritzer

And to whom or what were the lawful and the lawless passing on their responsibility and freedom when they passed them on to the state? Well, at least in the United States of America, a republic, they were passing on their freedom and attendant responsibility to a seemingly innocuous form of government, a representative government, a government of elected peers. But those peers, too, were human. They, too, only ruled as well as they were willing to form their consciences to the rule of “the laws of nature and of nature’s God,” and to act in accordance with those consciences. Besides, once a matter like the slaughter of the buffalo was referred to the state, the state, in regard for all its citizens, was required to rule at a higher degree of generality than that of the individual conscience with its single subject, so that the general law of the state would be less adaptable than the more immediate and specific law of the individual conscience. Ergo, the individual lost freedom. For at that point, even if circumstances presented a situation in which the individual could act in a certain way in good conscience according to “the laws of nature and of nature’s God,” he might no longer be able to do so according to the laws of the state, because he had relinquished his responsibility and freedom to the state and was the more subjected to it.

Tom considered a simple hypothetical case in this matter of the buffalo. In that case, those hunting the buffalo, lawful and lawless alike, would continue the slaughter despite the obvious signs of it being wrong, if in nothing else than the prodigious waste of meat. Elected representatives of the people, outraged at the waste and the precipitous reductions in the numbers of the animal, would eventually pass a law to forbid the killing of the buffalo. Given that scenario, the following case unfolds. A man out on the prairie comes upon a lame buffalo bull that has been left behind by its herd and is obviously going to die. The man has a family who, though they have some food and are not starving, could make good use of the meat from the bull. Now, however, according to the new law, the man with the family must not kill the bull, and so the lame buffalo moves on to die in some remote place where the meat will go to waste. Before the law, the man could have legally killed and butchered the bull and fed his family with the meat, and he could have done so in good conscience. Now, after the law, his only legal option is to not kill the bull. His conscience must now weigh the law against the hunger of his family and the waste of the meat. If the man decides in good conscience, after weighing the matter, that it is better to kill the bull to feed his hungry family rather than to let the meat rot, he has decided, in good conscience, to break the law. This is no small matter, because in a free society laws should exist to protect the unalienable rights of the citizens; therefore, the conscientious person, in good conscience, should normally obey the law.

In such a case, then, the law, the conscience, or both have been compromised. This conflict between conscience and law comes about as a result of the refusal of earlier hunters to form or obey their consciences. It is a result of those earlier hunters’ failure to rule themselves, a result of their having handed over responsibility to the state, which, by its nature, must rule in a more general way than the conscience. That the man in the hypothetical case is not a hunter illustrates another point: when citizens turn over responsibility to the state, not only do they turn over, with it, their own freedom, but also that of every other citizen, even the most conscientious.

Tom reflected on how his hypothetical case also illustrated the communal nature of man, the latent sacramentalism awaiting men’s acceptance of and cooperation with grace. “No man is an island,” wrote John Donne. “Never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.” If one is diminished, all are diminished. So John Donne let the world know in poetry, some two and a half centuries before, what the Church had been teaching for some sixteen centuries before that, having been taught it by Christ. Neither man nor a man lives in a vacuum. The act of a single man changes the world, the universe, regardless of how private or public the act. A good act has the capacity to yield good consequences far beyond the immediate effect; so does an evil act have a similar capacity to yield evil consequences. Therefore, for man (the creature in whom matter and spirit are combined in one nature, created with free will, in the very image of God), all his actions entail responsibility. Responsibility is a natural concomitant to human actions. To shirk responsibility is but an illusion, as the shirker is responsible for that shirking. And because human actions entail responsibility, each human action deserves its due consideration. When humans fail to accept the responsibility for their actions; when they refuse to give those actions due consideration; when, after such consideration, they refuse to act on the conclusions of an informed conscience, then events like the slaughter of the buffalo result.

Thus, Tom considered three broad categories of men: the conscientious, those who formed their consciences and acted according to them; the lawful, those who waited for the state to pass laws to legislate their behavior and thereby relinquished their freedom and its attendant responsibility to the state; and the lawless, those who had no respect for the law and would defy the law as they saw fit, until they were prevented by the state from doing so, thereby passing on all of their freedom and its attendant responsibility to the state. Consideration of these led Tom’s mind onto consideration of another category of man, call them the semi-lawful.

(continued in Part Three)