3 April 2012

Copyright © 2012 by P. A. Ritzer

I called in to the Laura Ingraham show on 22 March to comment on the issue of living together before marriage. Basically, I said: Women need to get a clue; if a man loves you, he’ll wait. As I used to ask my students: when you live together, how do you break up? You still have the rent and the electrical bill. You are more likely to remain in an unhealthy relationship. It comes down to the fact that love is not a feeling but an act of the will. It is a giving of the self that involves commitment. Feelings rise and fall, that is why you need commitment.

All we need to do, especially during Holy Week, is to take a look at a crucifix: the greatest act of love ever, and it did not feel very good.

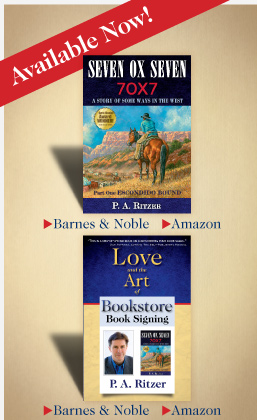

In Seven Ox Seven, Part One: Escondido Bound, Tom has to grapple with the question of love in light of romantic feelings that rise up in response to meeting a beautiful woman. Here is how he works it out in pages 82-86.

Copyright © 2007 by P. A. Ritzer

Julie flooded back—from where she had been occupying a good deal of the area behind it—to the forefront of Tom’s mind. In truth, she had occupied the greater part of his mind for most of the time since he had first seen her, and had at least wafted around somewhere in the back or bottom of his mind when she had not been occupying the greater part. It was not as if he actively thought of her. He did not need to think of her. It was less voluntary than that. He would have had to think to keep her out. There was a naturalness to the way she flooded his mind. Thinking of her was a natural reaction to the stimulus of her, and that thought had a naturally sensual character to it. The natural scent of her hair and skin, subtly enhanced by perfume, again delighted his sense of smell, in memory, intoxicating his mind through that most evocative of the senses. Her slender, lithe figure and the way that she moved played upon him in a way that no dance or drama could or, for that matter, could any imaginable movement of even the most graceful of the creatures of land, sky, or sea. Again he saw her eyes and, starting with those portals open wide to him, again ventured upon that journey into her beauty. Again her rich silken hair rested against the side of his face, as it had when they had danced; again the softness of her cheek glided beneath the light brush of his hand; again her delicate hands lightly enclosed his own.

He chuckled at how she had immediately attracted him and at how she still had a sensual hold on his mind. She was not the first to so affect him, and he doubted that she would be the last. He knew, from experience, that her absence would allow time to continually diminish the superficial though pervasive place she presently held in his mind, and he knew that, in this case, absence was the most prudent policy.

To get involved with a girl like Julie would be to give himself over to insecurity, because, since they did not appear to share common values, she could just as easily be interested in any other man who suited her (and probably would be), and he in any other woman. Julie was pretty enough to demand as much commitment as the willing man could afford, however illicit. Her knowledge of her power over men as an object of desire, and the pleasure such power obviously gave her, would only add to the insecurity of the relationship, as it would keep her ever watchful for that future man, better than the rest, who, too, would fall prey to her beauty and her charms. Judging from what he had seen of her values, Tom knew that he would not be this ultimate man, and he wondered whether any man ever would be, before her beauty would gradually succumb to the cosmetic applications so evident, at the Lady Gay, upon the faces of older members of her occupation. Regardless, such insecurity in a relationship could well lead to possessiveness or, paradoxically, to its contrary, disregard. Possessiveness could eventually lead to anger and resentment, disregard to indifference.

Tom considered further the development of a relationship founded on such shallow footings. How many times had he seen a man fall “head over heels” for a woman, only to see him, after that relationship had ended (and the fellow had been all but broken in half), fall equally in love with another woman nothing like the last. Such a thing could not then be love, Tom maintained, but some baser attraction. Love, instead, elevates desire between a man and a woman to its proper place, in a way that sets the human apart from the horse or the cow. Love elevates that desire into a consciousness of the need for moral and practical compatibility, which does not allow one to fool oneself into believing that selfish obsession with another can be love. This special love between a man and a woman must then require something of reason, which sets the human apart from the beast, to elevate this desire. The human creature must let reason rule desire and let love rule reason for them to be properly directed. Such is required by the dignity appropriate to the rational creature.

Therefore, Tom would never have considered that it was love that kept Julie in his mind. He had seen some men—and not just the young fellows fresh away from home and under the influence of drink—make that mistake often enough. But Tom knew that any fellow who would believe that he was in love in such a case, or even in a case more involved though equally shallow, was missing something. Otherwise, how could a man feel similar romantic feelings for different women, very unlike each other and of very different minds from the man himself?

No, such could not be love but merely infatuation. Tom knew love, and he would not have elevated infatuation to that height. It was because he knew love that he was also wary of over-romanticizing love between a man and woman. Love was plainer than glamorized infatuation, and yet, more profoundly beautiful in its plainness. It had its share of hardship, hard work, and pain. Love had a nakedness about it, compared to which the nakedness of infatuation was but a woefully shallow imitation. The nakedness of love could not be satisfied by the merely sensual. The nakedness of love demanded far more because it was far more: because it was the complete exposure, the complete sharing, the complete gift of the self, not just of the body. (And, in truth, given that the body is an essential component of human nature, one could never truly share the body without, at least to some degree, sharing the self, licitly, to one’s benefit, or illicitly, to one’s detriment.) The nakedness of love demanded commitment, with all that that word denoted and connoted, and a commitment not just to the other, but to the Other, Who is the Source of all love, Who is Love itself.

This awareness, on Tom’s part, always brought him around to his belief that there must be far more than just the sensual attraction between a man and a woman before it is appropriate to move further into the sensual realm of the relationship. There must be something profound that puts the sensual in its proper place and elevates it. There must be a singular affinity between the minds and souls of the man and woman, an affinity that draws them toward the commitment of love. There it was again, commitment, an act of the will, an act of the will that is the gift of the self. That is love: an act of the will that is the gift of the self! The commitment of love, in this singular case, must be Matrimony, the only commitment that, as a sacrament, provides the grace for a man and woman to share the nakedness of the Garden of Eden while yet in a fallen world. The grace of the sacrament assures that, rather than become a selfish taking, the sensual intimacy can be a selfless giving: to spouse, to God, to the children thus begotten. Hence, the Sacrament of Matrimony is the only commitment worthy of the ultimate sensual intimacy, an intimacy through which a man and woman become one body and, as such, enjoy the profound privilege and responsibility of participating in and sharing in God’s creation of another human being. It is in this commitment of the Sacrament of Matrimony that a man and woman are most capable, by design, of accepting their responsibility to raise to adulthood the human beings created through their union.

Given all that, Tom believed that it should follow, then, that a man should test his attraction to a woman for that affinity that draws a man and a woman into the Sacrament of Matrimony. He should do so because the attraction could lead to union, and union to procreation. The procreative result of this union is another human being, another material and spiritual creature with the capacity of union with the Infinite. Thus, the union of man and woman must command a most profound respect and commitment, because the procreation and upbringing of the product of that union, a child with a supernatural destiny, must carry a most profound responsibility.

He knew that no such affinity could exist between Julie and him. And yet she remained in his mind. He saw again the lose strands of her hair around her pretty ear and against her graceful neck. He saw again those long lashes and looked into those dark eyes. And again he knew that he could have been lost in those eyes, and that, past a certain point, he could have dissolved into her and enjoyed great pleasure in doing so, but for some little guide in him, a guide that could reach out and offer him the opportunity to return to shore from those waters into which he had begun to wade. Ah, but for this guide, conscience, what the contemporary Briton John Henry Newman would call “the aboriginal vicar of Christ.” Yes, but for this guide, what further evil might be introduced into this world under the guise of pleasure.

In this way, Tom’s mind examined the reality of the day against revealed truths and personal conclusions. That examination was part of a river of analytical thought that flowed through his mind seemingly involuntarily and almost incessantly. This flow of analytical thought was something Tom took for granted: he knew no other way.

“Hmph,” Tom sighed out loud, in a kind of muffled chuckle. “All this from dancin’ with a dancehall girl,” he thought.

But he knew it was more than that. All human relationships have a beginning, and how and why they begin determine to greater and lesser degrees how and where they proceed. Julie may not have technically been a cyprian, like some of the dancehall girls, but she saw no problem with accepting pay to show her affections. And Tom knew that once a person decided that her affections were for sale, the object of those affections would be the highest bidder, whether the bid was in money or some other variety of tender.

Nevertheless, though he had thus disposed of this potential relationship, it was the nature of Tom’s mind that, no matter what other thoughts ran through it, thoughts of Julie drifted around behind them and, often enough, advanced to the front, until he fell off to sleep.

Revisiting Dr. Seuss In Parenthood (Part One)

5 January 2012

The following commentary first appeared in Saint Austin Review, July/August 2005. It appears here with some revisions. Quotations in quotation marks and block quotes are from the works being considered.

In this election year, we might give special attention to the case of Yertle the Turtle and consider well the growing weight of government and taxation, especially considering the founders’ conviction that it must be a limited government–as established with the Constitution, “deriving [its] just powers from the consent of the governed” (as the Declaration of Independence would have it)–that best secures the “unalienable rights” with which our Creator has endowed us.

Copyright © 2003 by P. A. Ritzer

I remember my brother saying, years ago, that he looked forward to having children of his own, so that he could again watch old Disney movies. I, for my part, in my parenthood, have discovered the joy of revisiting Dr. Seuss and sharing his works, his stories, his words with my children.

This is not my first revisiting. The birth of my nephew and godson in 1990 opened the door for the first revisiting, which went so far as to include sharing with him and his parents a breakfast of green eggs and ham. It was during this first re-acquaintance that I remember declaring that Dr. Seuss was the Shakespeare for children. This declaration, besides being inspired by an adult appreciation for the genius of these works that I had so enjoyed as a child, may also have been an enlightened response to a long-remembered concern, voiced by my parents, and possibly initiated by my teacher, that at second, third, or fourth grade (some grade that was still on the first floor of Sacred Hearts School), perhaps I was too old to be reading Dr. Seuss. My youthful appreciation for these works has since been further vindicated, at least in my eyes, by the discovery that these classics were prescribed for my wife, long before she met me, to alleviate the stress of medical school exams, by a good friend and classmate, with whom she read the works in a stairwell amidst their echoing laughter. The prescriber is now a psychiatrist for both children and adults.

I offer no blanket endorsement or recommendation of the thought and works of Theodor Seuss Geisel. I do not know his thought and have not read all his works, nor have I revisited all his works which I read as a boy. But rather, what I wish to do is to share, as an adult and parent who struggles to live a Christian life in our modern world, an appreciation for the values expressed in at least some of the words, stories, and works of Dr. Seuss.

Certainly, in Green Eggs and Ham the reader is taught a lesson about deciding to dislike foods before one tries them, but does not the persistent Sam eventually wear down the nameless green-eggs-and-ham-hater’s pride- and ignorance-based prejudice, so that he might lead a fuller life with his discovery: “’Say! I like green eggs and ham! I do! I like them, Sam-I-am!’” Thus, the changed fellow can come to the grateful conclusion: “’I do so like green eggs and ham! Thank you! Thank you, Sam-I-am!’”

And, in our culture in which the words nip, tuck, and augmentation have become commonplace, might not the young reader benefit from considering the case of Gertrude McFuzz, a “girl-bird” who “had the smallest plain tail ever was. One droopy-droop feather. That’s all that she had. And, oh! That one feather made Gertrude so sad,” when she compared herself to “a fancy young birdie named Lolla-Lee-Lou,” who “instead of one feather behind, she had two!” This state of affairs leads a jealous Gertrude to one day shout in anger, “‘This just isn’t fair! I have one! She has two! I MUST have a tail just like Lolla-Lee-Lou!'”

Despite the admonition of her wise uncle Doctor Dake, who assures her, “’Your tail is just right for your kind of a bird,’” she throws tantrums, until he tells her of the pills of the pill-berry vine, which will make her tail grow. And although one pill gives her tail another feather, “exactly like Lolla-Lee-Lou,” she decides to “grow a tail better than Lolla-Lee-Lou.” And she does, by gobbling all the pill-berries down. She grows a tail so stupendous that “that bird couldn’t fly! Couldn’t run! Couldn’t walk!”

It takes her uncle and his assistants two weeks to fly Gertrude home. And Dr. Seuss relates:

And how much smarter or wiser might the young reader be after considering the case of Yertle the Turtle, king of the Pond on the Isle of Sala-ma-Sond, where “the turtles had everything turtles might need. And they were all happy. Quite happy indeed.”

So, Yertle begins to build a higher throne on the backs of his subjects, by commanding the turtles to stack themselves up, one on top of the other, beneath him, so that Yertle can see more and exclaim: “’I’m Yertle the Turtle! Oh, marvelous me! For I am the ruler of all that I see!’”

But the burden on the common folks grows to be too much to bear, so that “from below in the great heavy stack, [comes] a groan from that plain little turtle named Mack,” who petitions the king from his distress at the bottom of the stack, “’I know, up on top you are seeing great sights, But down at the bottom we, too, should have rights.’”

By now, though, the power-drunk Yertle has lost all sense of proportion, and after silencing Mack, he begins to call for more turtles that he might build his throne higher than the moon, when:

And from that throne, shaken by the common movement of the lowest subject upon which his corrupt foundation of exploitation is built, falls the mighty Yertle, “that Marvelous he,” into the depths of the mud. And “that was the end of the Turtle King’s rule!” The tyrant is thus deposed, “And the turtles, of course . . . all the turtles are free As turtles and, maybe, all creatures should be.”

(to be continued in Part Two)