5 January 2012

The following commentary first appeared in Saint Austin Review, July/August 2005. It appears here with some revisions. Quotations in quotation marks and block quotes are from the works being considered.

In this election year, we might give special attention to the case of Yertle the Turtle and consider well the growing weight of government and taxation, especially considering the founders’ conviction that it must be a limited government–as established with the Constitution, “deriving [its] just powers from the consent of the governed” (as the Declaration of Independence would have it)–that best secures the “unalienable rights” with which our Creator has endowed us.

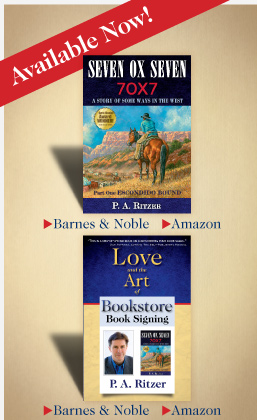

Copyright © 2003 by P. A. Ritzer

I remember my brother saying, years ago, that he looked forward to having children of his own, so that he could again watch old Disney movies. I, for my part, in my parenthood, have discovered the joy of revisiting Dr. Seuss and sharing his works, his stories, his words with my children.

This is not my first revisiting. The birth of my nephew and godson in 1990 opened the door for the first revisiting, which went so far as to include sharing with him and his parents a breakfast of green eggs and ham. It was during this first re-acquaintance that I remember declaring that Dr. Seuss was the Shakespeare for children. This declaration, besides being inspired by an adult appreciation for the genius of these works that I had so enjoyed as a child, may also have been an enlightened response to a long-remembered concern, voiced by my parents, and possibly initiated by my teacher, that at second, third, or fourth grade (some grade that was still on the first floor of Sacred Hearts School), perhaps I was too old to be reading Dr. Seuss. My youthful appreciation for these works has since been further vindicated, at least in my eyes, by the discovery that these classics were prescribed for my wife, long before she met me, to alleviate the stress of medical school exams, by a good friend and classmate, with whom she read the works in a stairwell amidst their echoing laughter. The prescriber is now a psychiatrist for both children and adults.

I offer no blanket endorsement or recommendation of the thought and works of Theodor Seuss Geisel. I do not know his thought and have not read all his works, nor have I revisited all his works which I read as a boy. But rather, what I wish to do is to share, as an adult and parent who struggles to live a Christian life in our modern world, an appreciation for the values expressed in at least some of the words, stories, and works of Dr. Seuss.

Certainly, in Green Eggs and Ham the reader is taught a lesson about deciding to dislike foods before one tries them, but does not the persistent Sam eventually wear down the nameless green-eggs-and-ham-hater’s pride- and ignorance-based prejudice, so that he might lead a fuller life with his discovery: “’Say! I like green eggs and ham! I do! I like them, Sam-I-am!’” Thus, the changed fellow can come to the grateful conclusion: “’I do so like green eggs and ham! Thank you! Thank you, Sam-I-am!’”

And, in our culture in which the words nip, tuck, and augmentation have become commonplace, might not the young reader benefit from considering the case of Gertrude McFuzz, a “girl-bird” who “had the smallest plain tail ever was. One droopy-droop feather. That’s all that she had. And, oh! That one feather made Gertrude so sad,” when she compared herself to “a fancy young birdie named Lolla-Lee-Lou,” who “instead of one feather behind, she had two!” This state of affairs leads a jealous Gertrude to one day shout in anger, “‘This just isn’t fair! I have one! She has two! I MUST have a tail just like Lolla-Lee-Lou!'”

Despite the admonition of her wise uncle Doctor Dake, who assures her, “’Your tail is just right for your kind of a bird,’” she throws tantrums, until he tells her of the pills of the pill-berry vine, which will make her tail grow. And although one pill gives her tail another feather, “exactly like Lolla-Lee-Lou,” she decides to “grow a tail better than Lolla-Lee-Lou.” And she does, by gobbling all the pill-berries down. She grows a tail so stupendous that “that bird couldn’t fly! Couldn’t run! Couldn’t walk!”

It takes her uncle and his assistants two weeks to fly Gertrude home. And Dr. Seuss relates:

And then it took almost another week more

To pull out those feathers. My! Gertrude was sore!

And, finally, when all the pulling was done,

Gertrude, behind her, again had just one . . .

That one little feather she had as a starter.

But now that’s enough, because now she is smarter.

And how much smarter or wiser might the young reader be after considering the case of Yertle the Turtle, king of the Pond on the Isle of Sala-ma-Sond, where “the turtles had everything turtles might need. And they were all happy. Quite happy indeed.”

They were . . . until Yertle, the king of them all,

Decided the kingdom he ruled was too small.

“I’m ruler,” said Yertle, “of all that I see.

But I don’t see enough. That’s the trouble with me.”

So, Yertle begins to build a higher throne on the backs of his subjects, by commanding the turtles to stack themselves up, one on top of the other, beneath him, so that Yertle can see more and exclaim: “’I’m Yertle the Turtle! Oh, marvelous me! For I am the ruler of all that I see!’”

But the burden on the common folks grows to be too much to bear, so that “from below in the great heavy stack, [comes] a groan from that plain little turtle named Mack,” who petitions the king from his distress at the bottom of the stack, “’I know, up on top you are seeing great sights, But down at the bottom we, too, should have rights.’”

By now, though, the power-drunk Yertle has lost all sense of proportion, and after silencing Mack, he begins to call for more turtles that he might build his throne higher than the moon, when:

That plain little turtle below in the stack,

That plain little turtle whose name was just Mack,

Decided he’d taken enough. And he had.

And that plain little lad got a little bit mad

And that plain little Mack did a plain little thing,

He burped!

And his burp shook the throne of the king!

And from that throne, shaken by the common movement of the lowest subject upon which his corrupt foundation of exploitation is built, falls the mighty Yertle, “that Marvelous he,” into the depths of the mud. And “that was the end of the Turtle King’s rule!” The tyrant is thus deposed, “And the turtles, of course . . . all the turtles are free As turtles and, maybe, all creatures should be.”

(to be continued in Part Two)

Revisiting Dr. Seuss In Parenthood (Part One)

5 January 2012

The following commentary first appeared in Saint Austin Review, July/August 2005. It appears here with some revisions. Quotations in quotation marks and block quotes are from the works being considered.

In this election year, we might give special attention to the case of Yertle the Turtle and consider well the growing weight of government and taxation, especially considering the founders’ conviction that it must be a limited government–as established with the Constitution, “deriving [its] just powers from the consent of the governed” (as the Declaration of Independence would have it)–that best secures the “unalienable rights” with which our Creator has endowed us.

Copyright © 2003 by P. A. Ritzer

I remember my brother saying, years ago, that he looked forward to having children of his own, so that he could again watch old Disney movies. I, for my part, in my parenthood, have discovered the joy of revisiting Dr. Seuss and sharing his works, his stories, his words with my children.

This is not my first revisiting. The birth of my nephew and godson in 1990 opened the door for the first revisiting, which went so far as to include sharing with him and his parents a breakfast of green eggs and ham. It was during this first re-acquaintance that I remember declaring that Dr. Seuss was the Shakespeare for children. This declaration, besides being inspired by an adult appreciation for the genius of these works that I had so enjoyed as a child, may also have been an enlightened response to a long-remembered concern, voiced by my parents, and possibly initiated by my teacher, that at second, third, or fourth grade (some grade that was still on the first floor of Sacred Hearts School), perhaps I was too old to be reading Dr. Seuss. My youthful appreciation for these works has since been further vindicated, at least in my eyes, by the discovery that these classics were prescribed for my wife, long before she met me, to alleviate the stress of medical school exams, by a good friend and classmate, with whom she read the works in a stairwell amidst their echoing laughter. The prescriber is now a psychiatrist for both children and adults.

I offer no blanket endorsement or recommendation of the thought and works of Theodor Seuss Geisel. I do not know his thought and have not read all his works, nor have I revisited all his works which I read as a boy. But rather, what I wish to do is to share, as an adult and parent who struggles to live a Christian life in our modern world, an appreciation for the values expressed in at least some of the words, stories, and works of Dr. Seuss.

Certainly, in Green Eggs and Ham the reader is taught a lesson about deciding to dislike foods before one tries them, but does not the persistent Sam eventually wear down the nameless green-eggs-and-ham-hater’s pride- and ignorance-based prejudice, so that he might lead a fuller life with his discovery: “’Say! I like green eggs and ham! I do! I like them, Sam-I-am!’” Thus, the changed fellow can come to the grateful conclusion: “’I do so like green eggs and ham! Thank you! Thank you, Sam-I-am!’”

And, in our culture in which the words nip, tuck, and augmentation have become commonplace, might not the young reader benefit from considering the case of Gertrude McFuzz, a “girl-bird” who “had the smallest plain tail ever was. One droopy-droop feather. That’s all that she had. And, oh! That one feather made Gertrude so sad,” when she compared herself to “a fancy young birdie named Lolla-Lee-Lou,” who “instead of one feather behind, she had two!” This state of affairs leads a jealous Gertrude to one day shout in anger, “‘This just isn’t fair! I have one! She has two! I MUST have a tail just like Lolla-Lee-Lou!'”

Despite the admonition of her wise uncle Doctor Dake, who assures her, “’Your tail is just right for your kind of a bird,’” she throws tantrums, until he tells her of the pills of the pill-berry vine, which will make her tail grow. And although one pill gives her tail another feather, “exactly like Lolla-Lee-Lou,” she decides to “grow a tail better than Lolla-Lee-Lou.” And she does, by gobbling all the pill-berries down. She grows a tail so stupendous that “that bird couldn’t fly! Couldn’t run! Couldn’t walk!”

It takes her uncle and his assistants two weeks to fly Gertrude home. And Dr. Seuss relates:

And how much smarter or wiser might the young reader be after considering the case of Yertle the Turtle, king of the Pond on the Isle of Sala-ma-Sond, where “the turtles had everything turtles might need. And they were all happy. Quite happy indeed.”

So, Yertle begins to build a higher throne on the backs of his subjects, by commanding the turtles to stack themselves up, one on top of the other, beneath him, so that Yertle can see more and exclaim: “’I’m Yertle the Turtle! Oh, marvelous me! For I am the ruler of all that I see!’”

But the burden on the common folks grows to be too much to bear, so that “from below in the great heavy stack, [comes] a groan from that plain little turtle named Mack,” who petitions the king from his distress at the bottom of the stack, “’I know, up on top you are seeing great sights, But down at the bottom we, too, should have rights.’”

By now, though, the power-drunk Yertle has lost all sense of proportion, and after silencing Mack, he begins to call for more turtles that he might build his throne higher than the moon, when:

And from that throne, shaken by the common movement of the lowest subject upon which his corrupt foundation of exploitation is built, falls the mighty Yertle, “that Marvelous he,” into the depths of the mud. And “that was the end of the Turtle King’s rule!” The tyrant is thus deposed, “And the turtles, of course . . . all the turtles are free As turtles and, maybe, all creatures should be.”

(to be continued in Part Two)