5 January 2012

The following commentary first appeared in Saint Austin Review, July/August 2005. It appears here with some revisions. Quotations in quotation marks and block quotes are from the works being considered.

In this election year, we might give special attention to the case of Yertle the Turtle and consider well the growing weight of government and taxation, especially considering the founders’ conviction that it must be a limited government–as established with the Constitution, “deriving [its] just powers from the consent of the governed” (as the Declaration of Independence would have it)–that best secures the “unalienable rights” with which our Creator has endowed us.

Copyright © 2003 by P. A. Ritzer

I remember my brother saying, years ago, that he looked forward to having children of his own, so that he could again watch old Disney movies. I, for my part, in my parenthood, have discovered the joy of revisiting Dr. Seuss and sharing his works, his stories, his words with my children.

This is not my first revisiting. The birth of my nephew and godson in 1990 opened the door for the first revisiting, which went so far as to include sharing with him and his parents a breakfast of green eggs and ham. It was during this first re-acquaintance that I remember declaring that Dr. Seuss was the Shakespeare for children. This declaration, besides being inspired by an adult appreciation for the genius of these works that I had so enjoyed as a child, may also have been an enlightened response to a long-remembered concern, voiced by my parents, and possibly initiated by my teacher, that at second, third, or fourth grade (some grade that was still on the first floor of Sacred Hearts School), perhaps I was too old to be reading Dr. Seuss. My youthful appreciation for these works has since been further vindicated, at least in my eyes, by the discovery that these classics were prescribed for my wife, long before she met me, to alleviate the stress of medical school exams, by a good friend and classmate, with whom she read the works in a stairwell amidst their echoing laughter. The prescriber is now a psychiatrist for both children and adults.

I offer no blanket endorsement or recommendation of the thought and works of Theodor Seuss Geisel. I do not know his thought and have not read all his works, nor have I revisited all his works which I read as a boy. But rather, what I wish to do is to share, as an adult and parent who struggles to live a Christian life in our modern world, an appreciation for the values expressed in at least some of the words, stories, and works of Dr. Seuss.

Certainly, in Green Eggs and Ham the reader is taught a lesson about deciding to dislike foods before one tries them, but does not the persistent Sam eventually wear down the nameless green-eggs-and-ham-hater’s pride- and ignorance-based prejudice, so that he might lead a fuller life with his discovery: “’Say! I like green eggs and ham! I do! I like them, Sam-I-am!’” Thus, the changed fellow can come to the grateful conclusion: “’I do so like green eggs and ham! Thank you! Thank you, Sam-I-am!’”

And, in our culture in which the words nip, tuck, and augmentation have become commonplace, might not the young reader benefit from considering the case of Gertrude McFuzz, a “girl-bird” who “had the smallest plain tail ever was. One droopy-droop feather. That’s all that she had. And, oh! That one feather made Gertrude so sad,” when she compared herself to “a fancy young birdie named Lolla-Lee-Lou,” who “instead of one feather behind, she had two!” This state of affairs leads a jealous Gertrude to one day shout in anger, “‘This just isn’t fair! I have one! She has two! I MUST have a tail just like Lolla-Lee-Lou!'”

Despite the admonition of her wise uncle Doctor Dake, who assures her, “’Your tail is just right for your kind of a bird,’” she throws tantrums, until he tells her of the pills of the pill-berry vine, which will make her tail grow. And although one pill gives her tail another feather, “exactly like Lolla-Lee-Lou,” she decides to “grow a tail better than Lolla-Lee-Lou.” And she does, by gobbling all the pill-berries down. She grows a tail so stupendous that “that bird couldn’t fly! Couldn’t run! Couldn’t walk!”

It takes her uncle and his assistants two weeks to fly Gertrude home. And Dr. Seuss relates:

And then it took almost another week more

To pull out those feathers. My! Gertrude was sore!

And, finally, when all the pulling was done,

Gertrude, behind her, again had just one . . .

That one little feather she had as a starter.

But now that’s enough, because now she is smarter.

And how much smarter or wiser might the young reader be after considering the case of Yertle the Turtle, king of the Pond on the Isle of Sala-ma-Sond, where “the turtles had everything turtles might need. And they were all happy. Quite happy indeed.”

They were . . . until Yertle, the king of them all,

Decided the kingdom he ruled was too small.

“I’m ruler,” said Yertle, “of all that I see.

But I don’t see enough. That’s the trouble with me.”

So, Yertle begins to build a higher throne on the backs of his subjects, by commanding the turtles to stack themselves up, one on top of the other, beneath him, so that Yertle can see more and exclaim: “’I’m Yertle the Turtle! Oh, marvelous me! For I am the ruler of all that I see!’”

But the burden on the common folks grows to be too much to bear, so that “from below in the great heavy stack, [comes] a groan from that plain little turtle named Mack,” who petitions the king from his distress at the bottom of the stack, “’I know, up on top you are seeing great sights, But down at the bottom we, too, should have rights.’”

By now, though, the power-drunk Yertle has lost all sense of proportion, and after silencing Mack, he begins to call for more turtles that he might build his throne higher than the moon, when:

That plain little turtle below in the stack,

That plain little turtle whose name was just Mack,

Decided he’d taken enough. And he had.

And that plain little lad got a little bit mad

And that plain little Mack did a plain little thing,

He burped!

And his burp shook the throne of the king!

And from that throne, shaken by the common movement of the lowest subject upon which his corrupt foundation of exploitation is built, falls the mighty Yertle, “that Marvelous he,” into the depths of the mud. And “that was the end of the Turtle King’s rule!” The tyrant is thus deposed, “And the turtles, of course . . . all the turtles are free As turtles and, maybe, all creatures should be.”

(to be continued in Part Two)

The Republican Convention and PBS

© 2012 by P. A. Ritzer

29 August 2012

As I watched one speaker after another intelligently and engagingly put the lie to the Obama and Democratic Party record and talking points, I had to wonder at the PBS team covering the event. First of all, I would have rather heard and seen Janine Turner and Nikki Haley and anyone else I missed when the PBS team deemed that their . . . what? . . . “commentary” and “analysis” should take priority over the contributions of the real players in this one-time event. Among other things, I wondered if the amply seasoned partisan commentators Gwen Ifill, Judy Woodruff, and Mark Shields, and their token conservative–so suited to the role that he writes for the New York Times and was once inspired to prophesy about an inevitable Obama presidency while staring at the crease in Obama’s pants–David Brooks still made a pretense of objectivity.

Regardless, I thought back to an earlier time when I was glad of PBS Republican Convention coverage. It was 1984, and I had finally landed on PBS after hurriedly clicking through the four available channels. Why the rush? Well, because I had noticed that, off in the distance behind John Chancellor droning on to Tom Brokaw, it appeared that Jack Kemp was speaking. No, the networks would not talk over one of the most dynamic and popular Republicans of the day. But, sure enough, when I landed on PBS, there was Kemp. But they would not do that to Jeane Kirkpatrick, the keynote. Sure they would, and at least John and Tom did. Again, I found her on PBS. So, two of the brightest stars of the night, including a brilliant woman who was at the time still a Democrat who would switch to the Republican Party the next year, were kept from the view of the public by tedious liberal commentary. I remember that Paul Harvey–this was still a few years before Rush Limbaugh burst onto the scene and signaled the beginning of the end of the liberal media monopoly, for now–the next day mentioned this abuse of power by the networks and how he would tune to PBS from that time on for coverage of the Republican Convention.

So, I did just that, as well. And during a later campaign, when MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour was the only news program that, despite its liberal bias, would at least bring on guests representing the opposing point of view, I watched their campaign coverage. I remember the glowing backgrounder report on the Democratic Party, stretching well past Martin Van Buren and Andrew Jackson and the Albany-Richmond Axis all the way back to Thomas Jefferson. No mention of slavery, the Dred Scott Decision, the Ku Klux Klan, lynching, the black codes, disfranchisement, Jim Crow, opposition to women’s suffrage. Huh. All right. Well, anyway, I looked forward to the backgrounder on the Republican Party. I believe it was Judy Woodruff who delivered it. As I remember, it started out with how “the modern Republican Party” started with Richard Nixon. What? Not conceived as a reaction to the Kansas-Nebraska Act and its extension of slavery? No Ripon? No Abraham Lincoln? No Emancipation Proclamation? No Frederick Douglass? No Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments? No civil rights laws? No Ulysses S. Grant? No Susan B. Anthony, women’s suffrage, and the Nineteenth Amendment? No Theodore Roosevelt? No Calvin Coolidge? No Dwight D. Eisenhower? No century-long battle against the Democrats to secure civil rights for African-Americans? No, it was Richard Nixon. The “modern” Republican Party started with the most discredited, rightly or wrongly, Republican president in history. How convenient.

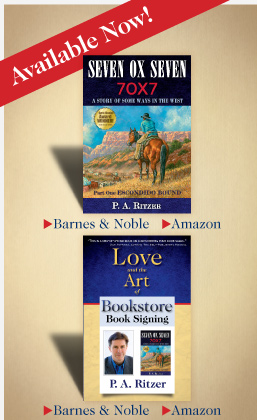

But people are beginning to know better today. The new media is shredding the monopoly of the liberal media, though many–including the Republican establishment–have not yet fully realized it. And thus people have access to sources that belie what was spoon-fed to the public by the old media. And the media did look old on that PBS panel. Nevertheless, they still try, and feisty old Mark Shields thought he had really got one of the guests when he pointed out that the Morrill Act and the Homestead Act, both first passed in 1862, were Republican “government programs.” Yes, but these were not liberal Democratic programs like those of the New Deal and the Great Society designed to create dependence on an ever-expanding government. To illustrate my point, I refer to the following excerpt about the Homestead Act from Seven Ox Seven, Part One: Escondido Bound, pp. 55-56:

In the case of homesteading, the government made available public property, not confiscated from its citizens, to those citizens who could benefit from it and were willing and able to improve the land and bring forth its produce to augment the production of the nation. The government did not retain ownership of the land, but turned over ownership to the private citizen after the citizen had earned it and, in the process, proven himself suited and worthy to own it, benefiting the nation in the process. Thus, whereas through an income tax the government confiscated private property, through homesteading the government created private property by distributing parcels of the public domain to those who earned them. And, after all, was not the United States of America a nation of people in a geographic area with a system of government devised by that people: “We the people of the United States of America.” The land did not belong to the government: it belonged to the nation, a nation of people. The representative government of that nation, that “government of the people, by the people, for the people,” merely fulfilled the role of administering the nation’s public land. Since the land of the nation belonged to the people of the nation, and since the land in question did not belong to any particular citizens, why not make it available to the greatest number of citizens or potential citizens (especially those without the capital to purchase it) who would earn ownership of it by improving that land and making a living from it, toward the end of making them productive, propertied citizens? Why not, where it was feasible, open the land to ownership by those citizens who would prove their worthiness to so own through their commitments of time and effort and their achieved improvement of the land? If an applicant could not improve it, could not make it, then he did not earn the property. The property would be open for another to attempt to earn. This process would continue until those who earned ownership of the land were those most suited to inhabiting and making a living from it. It was an investment of the nation in itself, to place upon the land those most suited to bring forth its produce. Was it not in the best interest of the nation to place upon the nation’s land the greatest number of deserving people who could benefit from it, rather than allow the land to be concentrated in monopolies by persons or entities? Did it not give more citizens a stake in the nation, give them more reason to participate as free citizens? And this was not a giveaway. It was a sale, in which those with little or no capital could purchase land through their labor by “proving up.” And it would not contribute to dependence but to independence, as those who earned it were awarded ownership. And it was Republican. Though the roots of homesteading were older than the Republican party and could be traced back to a proposal by Thomas Hart Benton in 1825, and even further back to Thomas Jefferson, who had said, “as few as possible should be without a little parcel of land,” it was the Republicans who had made it law. It had been a plank in the Republican party platform, and Republican Galusha Grow of Pennsylvania had authored the homestead bill that President Lincoln had signed into law in 1862. Lincoln had succinctly said of the policy, “I am in favor of cutting the wild lands into parcels, so that every poor man may have a home.”